A Simple Yet Provocative Question

What part of the Internal Revenue Code says that depreciation is mandatory? Tax attorneys, certified public accountants, tax professionals, and even tax professors will often cite Sections 167 and 263 of the Internal Revenue Code.

Section 167 of the Internal Revenue Code state that “[t]here shall be allowed as a depreciation deduction a reasonable allowance for the exhaustion, wear and tear (including reasonable allowance for obsolescence) of property used in the trade or business or of property held for the production of income.” This section of the Code says a taxpayer shall be allowed to depreciate certain property, but nowhere in the statute is there any suggestion that depreciation is mandatory.

In response, tax professionals will then explain how expenditures for “capital assets” are different from ordinary and necessary expenses for day-to-day costs, but they will still fail to cite specific Congressionally enacted statutory language to support their logic. At best, they will cite to Section 263, which is titled “Capital expenditures” and under the Internal Revenue Code, Subtitle A, Chapter 1, Subchapter B, Part IX, titled “Items Not Deductible.”

However, Section 263 merely states that “[n]o deduction shall be allowed for… [a]ny amount paid out for new buildings or for permanent improvements of betterments made to increase the value of any property or estate.” This is referencing and applicable only to “new buildings” and “permanent improvements” made with the specific intent to “increase the value” of said buildings. As such, it logically would not apply to the purchase of an existing building or permanent improvements made for a purpose other than to “increase the value,” such as to increase the safety of a stairway or add recreational facilities.

A Lack of Statutory Support

This dilemma of even experienced tax attorneys being unable to cite the specific Congressionally enacted statutory language for a tax concept illustrates why the U.S. Supreme Court has continually backtracked on its 1984 decision in Chevron v. NRDC to wholesale defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute its tasked with enforcing.[1] Moreover, it explains why the U.S. Supreme Court in 2024 is considering completely abrogating the Chevron decision in the cases of Loper Bright Enterprises, Inc. v. Raimondo and, jointly, Relentless, Inc. v. Department of Commerce. The U.S. Supreme Court is displaying its frustration that the body of tax law has become far too complex with concepts and rules being read into the statute that are not actually there.

For example, in 2010, the U.S. Tax Court held that if a statute’s language is clear and unambiguous, it forecloses the ability of the U.S. Treasury to promulgate gap-filling regulations.[2] As such, according to the U.S. Tax Court, regulations that go against the clear and unambiguous language in a statute are invalid as a matter of law.

The Supreme Court Blows the Whistle

Only two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court backed up this logic when it held, in U.S. v. Home Concrete & Supply, LLC, that a properly promulgated regulation that contradicted the plain meaning of a statutory term was invalid as a matter of law.[3] In that case, the IRS had imposed a Congressionally enacted penalty for omission of income on the grounds that the taxpayer had overstated his basis thereby resulting in less gain reported on the sale of an asset. The IRS argued that the inflated basis logically reduced reportable gain thereby constituting a de facto omission of income. The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed and held that “omission” and “overstatement” were not only irreconcilable but direct opposites; omission is something left out whereas overstatement is something added in. Because the regulation contradicted the plain meaning of a term in the statute, it was deemed to be invalid as a matter of law. The penalty was reversed.

For most tax professionals, this case was merely about a penalty that was deemed invalid. But to legal scholars, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Home Concrete decision was monumental. How many regulations could now potentially be deemed invalid as a matter of law for going against the plain meaning of the statute? And did the Home Concrete case arguably abrogate prior U.S. Supreme Court cases that had previously upheld agency interpretations that had no actual supporting statutory text?

For example, in 1970, in Woodward v. Commissioner, the U.S. Supreme Court, deferring to “longstanding Treasury regulations,” held that “[s]ince the inception of the present federal income tax in 1913, capital expenditures have not been deductible.”[4] To support that assertion, the U.S. Supreme Court cited Section “IIB of the Income Tax Act of 1913, 38 Stat. 167” in Footnote 2.

The Income Tax Act of 1913, Section II, Subsection B, Paragraph 2, reads as follows:

“[I]n computing net income for the purpose of the normal tax, there shall be allowed as deductions… a reasonable allowance for the exhaustion, wear and tear of property arising out of its use or employment in the business … but no deduction shall be made for any amount of expense of restoring property or making good the exhaustion thereof for which an allowance is or has been made: Provided, That no deduction shall be allowed for any amount paid out for new buildings, permanent improvements, or betterments, made to increase the value of any property or estate.”

As you can see for yourself, there was no statutory text in 1913 to support the overly broad assertion that all capital expenditures are not deductible. Instead, the 1970 U.S. Supreme Court based its reasoning on “longstanding Treasury regulations,” but this rationale was expressly shot down 42 years later by the 2012 U.S. Supreme Court in Home Concrete.

The Full Impact of the Home Concrete Case

So what does it mean if Home Concrete abrogated the Woodward decision and its progeny? It means the Treasury regulations interpreting Section 167 and 263 are arguably invalid as a matter of law.

By its express terms, Section 263’s definition of capital expenditures is expressly limited to real estate. Not even the broadest interpretation of any statutory terms can support extending it to other items, such as a vehicle or computer.

By its express terms, Section 167 is permissive by stating there “shall be allowed” a depreciation deduction, which permits taxpayers to decide for themselves whether to spread a deduction over several years.

By its express terms, Section 168 merely provides the rules that apply to “the depreciation deduction provided by Section 167(a) for any tangible property.”[5]

By its express terms, Section 162 expressly states that there “shall be allowed as a deduction all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business.” Is it ordinary and necessary to incur expenses to acquire computers and printers? Yes. Is it ordinary and necessary to have a business vehicle? Yes.

This would mean that taxpayer can determine for themselves whether to fully deduct an ordinary and necessary expense in the year incurred or whether to spread it out over several years.

For example, pursuant to the IRS’s interpretation, if you had $30,000 of income but purchase a vehicle for $20,000 cash, you would have to mandatorily depreciate the vehicle over 5 years ($4,000 per year) leaving you with net taxable income of $26,000 ($30,000 income less $4,000 depreciation deduction).[6] In reality, you only have $10,000 ($30,000 minus the $20,000 cash purchase). At a tax rate of 20%, you would owe $5,200 in tax. In reality, that’s 52% of your net income.

Practical Conclusion

With the U.S. Supreme Court’s Home Concrete decision, you could fully expense the purchase under Section 162. As such, your net income in the example above would be $10,000 ($30,000 minus the $20,000 cash purchase). At a tax rate of 20%, your tax bill would be $2,000. Logical and mathematical versus the illogical result based on the old and arguably abrogated Woodward decision as well as a plethora of other cases from various circuit courts of appeal and district courts.[7]

Therefore, it is clear that there is Substantial Authority for the legal position that the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Home Concrete abrogated its prior Woodward decision and progeny thereby making depreciation optional.

Legal Disclosure

This article is not intended to be relied on for the purpose of preparing a tax return or establishing reasonable cause, good faith, or avoiding tax-related penalties under the Internal Revenue Code. For the latter, the requirements for written legal advice to establish reasonable cause for the avoidance of penalties are outlined in 31 C.F.R. § 10.37. It is improper and impermissible to rely on this article as legal or preparation advice. In the U.S. tax system, generally, only a paid consultation or formal written tax opinion can be used as an affirmative defense to penalties. Free consultations may not be relied upon as legal advice for the purpose of avoiding penalties. The objective of a free consultation is to determine the client’s issue, fact pattern, and whether the firm can provide a legally viable solution with a minimum of Substantial Authority to support it.

Confidence Level Disclosure

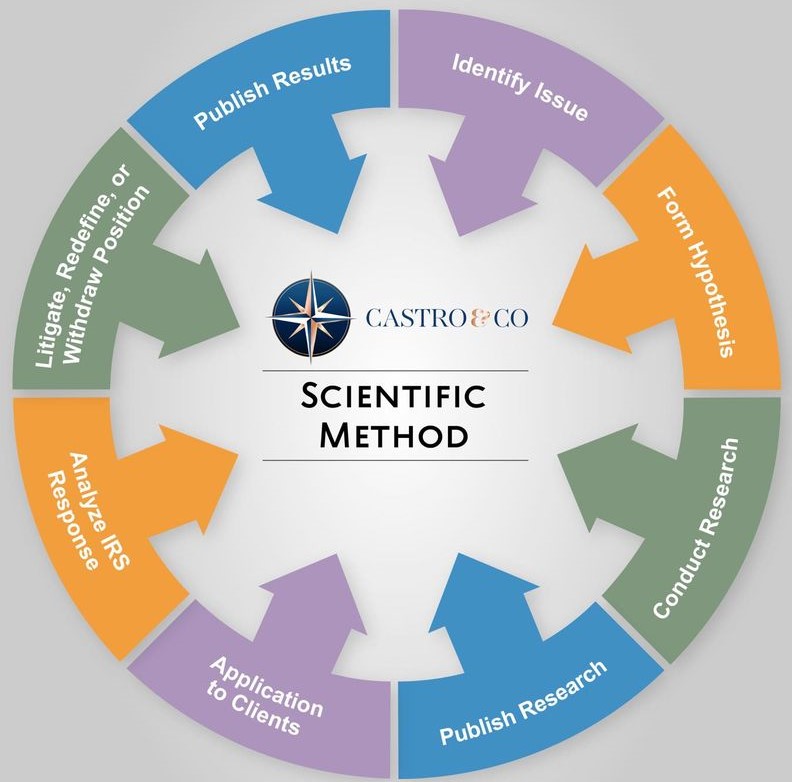

For over 3600 years, the scientific method has been used by innovative individuals as an empirical method of acquiring knowledge. In the world of tax law, it is no different. In some cases, we offer free consultations to identify the issue, form a hypothesis, conduct legal research to work toward developing a possible solution, publish our research, apply the legal theory to a client’s real-world situation, analyze the administrative response from the IRS, and then decide whether to litigate, redefine, or withdraw the position.

If the IRS points out something we had previously not considered and the legal position cannot be redefined to cure the issue, then we would withdraw the position and issue a notice to any clients to whom it applied. If, however, the position can be cured by redefining the position, then we will do so assuming the clients’ facts support the redefinition. This would, of course, entail contacting the client to seek clarification. If, however, we do not agree with the IRS response, then we will pursue litigation to seek judicial clarification in our favor.

The Scientific Method helps our tax system mature, develop, and improve by asking new questions and developing new interpretations of our tax code, answering previously unanswered questions, testing these legal theories in the federal judiciary, and eliminating ambiguity through judicial clarification. Judicial clarification even helps eliminate the need of tax attorneys who financially benefit from legal ambiguity. A fair and balanced tax system is one that is clear and concise with zero ambiguity. This can only be achieved through judicial clarification.

In the U.S. legal system, the "strength" of a legal interpretation can be quantified based on the amount of legal support for the interpretation. While a portion of this quantification is certainly subjective based on the reviewer’s legal interpretative philosophy, it is indisputable that a quantified range that encompasses all interpretative philosophies can be established. In some cases, this range can vary wildly. The importance of the level of legal authority is that it determines when penalties will and will not apply as well as when disclosure is and is not required to avoid said penalties. The range of levels of legal confidences are, from weakest to strongest, Reasonable Basis, Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, Should, and Will. In actual practice, a “Will” level opinion is never sought out by taxpayers since that would simply be a reiteration of basic textbook principles of the tax code. Likewise, a “Reasonable Basis” level opinion is rarely issued since, absent a compelling political or social purpose, it is highly unlikely to prevail in court. If, however, the topic of the “Reasonable Basis” opinion implicates a compelling political or social issue, such as the deduction for child care expenses, then our confidence in our ability to sway the federal judiciary increases, and we are, therefore, much more confident in asserting said legal position before the federal judiciary. This leaves only three confidence levels: Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, and Should. These are the three confidence levels within which our firm primarily operates.

A “Substantial Authority” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a 35 percent to 49 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “More Likely Than Not” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a greater than 50 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “Should” opinion, which is the threshold of opinion expressed in this letter, generally means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a chance greater than 70 percent of success on the merits. It is important to note that these quantifications themselves are hotly contested, which implicates “void of vagueness” concerns.

The confidence level of the legal interpretation expressed in this article is: Substantial Authority.

Bluebook Citation

John Anthony Castro, Who Said Depreciation Was Mandatory, Int’l Tax Online Law Journal (December 10, 2023) url.

Legal Citations

[1] See Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984)

[2] See Intermountain v. C.I.R., 134 T.C. 211 (2010).

[3] See U.S. v. Home Concrete & Supply, LLC, 132 S. Ct. 1836 (2012).

[4] 397 U.S. 572, 574 (1970).

[5] Even Section 179(a) states that a “taxpayer may elect to treat the cost of any section 179 property as an expense which is not chargeable to capital account.” This sentence implies that a taxpayer who is otherwise obligated to maintain a “capital account” can elect to not charge a cost to said account and instead fully deduct the expense. However, nowhere in the Code are individuals mandated to maintain capital accounts.

[6] Moreover, pursuant to 26 U.S.C. § 280F, “[t]he amount of the depreciation deduction for any taxable year for any passenger automobile” is limited to certain figures, but this is still if and only if you elect to depreciate to begin with.

[7] Tulia Feedlot, Inc. v. U.S., 513 F.2d 800, cert. denied 423 U.S. 947 (5th Cir. 1975) (capital expenditures must be amortized); Brooks v. C.I.R., 424 F.2d 116 (5th Cir. 1970) (expenses incurred to construct a capital asset are capital expenditures); Clark Oil & Ref. Corp. v. U.S., 326 F. Supp. 145 (E.D. Wis. 1971), aff’d, 473 F.2d 1217 (7th Cir. 1973) (If an expenditure is one which fits neither the precise terms of expense or capital expenditure, then expenditure is not deductible in computing federal income tax liability); U.S. v. General Bancshares Corp., 388 F.2d 184 (8th Cir. 1968) (whether expenses are ordinary and necessary and thus deductible or are capital in nature and must be depreciated depends on character of transaction to which they relate); Great Lakes Pipe Line Co. v. U.S., 352 F. Supp. 1159 (W.D. Mo. 1972), aff’d, 505 F.2d 735 (8th Cir. 1974) (If an expense is capital it cannot be deducted as an ordinary and necessary business expense for income tax purposes); U.S. v. Akin, 248 F.2d 742 (10th Cir. 1957) (Section 162 does not authorize a deduction for capital expenditures); Shutler v. U.S., 470 F.2d 1143 (10th Cir. 1972); Williams & Waddell, Inc. v. Pitts, 148 F. Supp. 778 (E.D.S.C. 1957) (Expenditures which are made to protect or to promote income taxpayer’s business, and which do not result in the acquisition of a capital asset, are deductible as “ordinary and necessary business expenses”); Ransburg v. U.S., 281 F. Supp. 324 (S.D. Ind. 1967) (Basic fundamental of this title is not to allow deduction of capital expenses from ordinary income but to offset such against capital gains, but Congress can and does digress from fundamental on granting tax relief); Simenstad v. U.S., 325 F. Supp. 1249 (N.D. Cal. 1971) (Expenditures in nature of capital outlays are not deductible as “ordinary and necessary business expenses”; capital expenditures, if deductible at all, must be amortized over the useful life of the asset).