Introduction

For the first 144 years since the founding of our country, it was illegal for a woman to vote. In the 1872 presidential election, Susan B. Anthony voted in New York. Because women did not have the right to vote, she was arrested, forced to face a widely publicized trial in court, and found guilty of illegally voting. Under the eyes of the law, she was a convicted criminal. For the next 34 years until her death, she campaigned for a constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote.

It was not until 13 years after her death that Congress, on June 4, 1919, voted in favor of granting women the right to vote with the requisite number of states ratifying the proposal on August 18, 1920. As a result, the United States Constitution was amended to unquestionably grant women the right to vote in any and all elections.

Nevertheless, discrimination on the basis of sex persisted for decades. One such notable example was only a few years later in 1939 when the United States Board of Tax Appeals, under Judge Clarence Opper, issued a shockingly sexist ruling that has continued to be cited for nearly a century without question.

The Genesis

In 1937, Henry and Lillie Smith were husband and wife. They were both employed on a full-time basis; very uncommon in those times. They engaged the services of nursemaids to care for their children and those services were performed outside the home; the modern equivalent of an infant daycare facility.

According to Section 24(a)(1) of the Revenue Act of 1936 (the law in effect at the time), Congress declared that in “computing net income, no deduction shall in any case be allowed in respect of personal, living, or family expenses.”[1] From the perspective of Mr. & Mrs. Smith, these expenses were not personal or family; rather, they were ordinary and necessary expenses to pursue a trade or business.

The Commissioner of Internal Revenue initiated an examination of the Smiths' 1937 federal income tax return. Upon examination, the Commissioner disallowed the deduction for child care expenses and issued a deficiency notice. Mr. & Mrs. Smith petitioned for judicial review before the U.S. Board of Tax Appeals in the case we now cite as Smith v. Commissioner.[2]

Smith v. Commissioner

Judge Clarence Opper presided over the case. In his ruling, he called “the working wife a new phenomenon.” This laid the foundation for a claim that this was not "ordinary." He explained that he was not prepared to declare that the care of children is anything “other than a personal concern” since the wife’s services as “custodian of the home and protector of its children are ordinarily rendered without monetary compensation.”[3] Judge Opper elaborated and explained that, in this case, “the wife has chosen to employ others to discharge her domestic function.” In other words, according to Judge Opper, because he viewed a woman’s natural function to be cleaning the home and caring for the children, it was, in his opinion, an inherently personal expenditure to hire others to perform her function. Therefore, the expenses were not deductible on that basis. On the basis of a shockingly discriminatory view of the role of women in our society.

This case shows that the reasoning for which the deductibility of child care expenses was denied was based upon an archaic view of the role of women in our society. In only a few short sentences, Judge Opper disgraced his role as a representative of the federal judiciary to declare that, because he considered a woman’s natural function to be the caring of children, it was an inherently personal expenditure to hire others to perform that function. It is upon that sexually discriminatory basis that Judge Opper declared child care expenses non-deductible personal expenses.

Legal Predicament

This case evidences that the genesis, origin, and reasoning behind the non-deductibility of child care expenses is based upon unconstitutional discrimination on the basis of sex in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In fact, one federal court already found that the prevailing interpretation of Section 262 “might impose a particular burden on working women.”[4] Of course it does. That was Judge Opper’s invidious intent.

And this case is not merely some obscure relic of our federal judicial history. The indisputably sexist Smith case has been cited as binding legal authority, without thorough analysis, in the federal judiciary 26 times[5] as recently as 2011 in Kuntz v. Commissioner.[6]

Current Law

Under the modern Section 262, Congress declared that “Except as otherwise expressly provided in this chapter [Sections 1 through 1400z-2], no deduction shall be allowed for personal, living, or family expenses.” Unlike the former provision, the modern provision leaves open the possibility of exceptions that may exist in other Code sections. Section 262 is, therefore, subordinate to other sections that may permit the deductibility of “personal, living, or family expenses,” such as Section 119 and 162. Nevertheless, focusing squarely on Section 262 for now, in order to determine whether an expense is a personal, living, or family expense, one must review all applicable case law. There are surprisingly only three on-point cases.

In Commissioner v. Moran, the court held that a personal expense exists when it is a type of expense that is generally incurred by all people.[7] Do all parents incur child care expenses to pursue a career? Absolutely not. In fact, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 35.8% of U.S. households had only one working parent.[8] Stated differently, more than 40 million family households have a homemaker parent that cares for the children on a full-time basis. Therefore, applying this rule as outlined Commissioner v. Moran, child care expenses are not of the type generally incurred by all people and, thus, would not be inherently personal family expenses. Therefore, in accordance with that rule, child care expenses would be deductible.

In Commissioner v. Doak, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit held that the blanket ban on personal and family expenses could only be overruled by statutory exceptions elsewhere in the Code.[9] Section 162 permits a deduction for “all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year in carrying on any trade or business.” In maintaining one’s employment, is it not ordinary to have someone watch your children? In fact, is it not necessary both for the workplace that does not permit children as well as the law that criminalizes leaving children unattended? Therefore, in accordance with that rule, child care expenses would be deductible.

In Northern Trust Company v. Cambell, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit added that it is not only the nature of the expense itself but also the proximate relation to business.[10] Do companies allow single working parents to bring their children to work? Is it not implied that, if you have children, you must secure the services of a competent person to supervise them? The U.S. government spends nearly $2.5 billion annually in tax credits and other subsidies to reward companies that provide on-site child care facilities because of its proximate relation to business. Therefore, in accordance with that rule, child care expenses would be deductible.

Conclusion

Based on the foregoing, it is our firm’s conclusion that Section 262, as applied to the deductibility of child care expenses, is unconstitutional as-applied. This is a much more narrowly focused constitutional challenge based on circumstances. In the event it somehow survives a constitutional challenge, it is our firm's conclusion that the expense is still deductible under Section 162 by virtue of the opening clause of Section 262 that states "except as otherwise" provided in the Chapter 1, Normal Taxes, which includes Section 162.

Therefore, we do not see a situation where, based on this legal approach, a denial of a deduction for child care expenses could be upheld in federal court.

Policy Considerations

In order to settle this issue, we call upon the White House to issue an Executive Order promulgating a temporary regulation declaring “Personal, living, and family expenses shall not include the cost of child care that is necessary for the purpose of maintaining employment but only where the employer does not provide child care facilities.”

Coupled with legislation modeled after the individual healthcare mandate, we propose mandating that companies with more than 25 employees must provide child care for their employees. This would save the U.S. government about $2.5 billion in tax subsidies it currently grants to promote child care.

Contact Our Firm

Contact our firm today to schedule a free consultation by clicking here to submit your information online and be contacted by our firm.

Legal Disclosure

This article is not legal advice. It is improper to rely on this article as legal advice. In the U.S. tax system, generally, only a paid consultation or formal written tax opinion can be used as an affirmative defense to penalties. Free consultations may not be relied upon as legal advice for the purpose of avoiding penalties. The objective of a free consultation is to determine the client’s issue, fact pattern, and whether the firm can provide a legally viable solution with a minimum of Substantial Authority to support it.

Confidence Level Disclosure

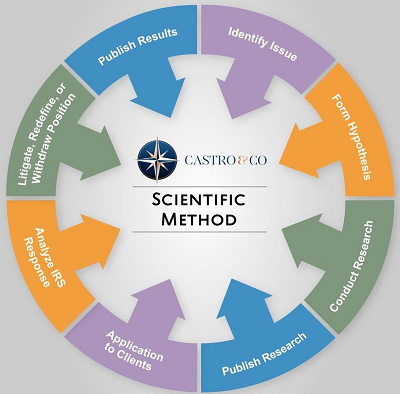

For over 3600 years, the scientific method has been used by innovative individuals as an empirical method of acquiring knowledge. In the world of tax law, it is no different. In some cases, we offer free consultations to identify the issue, form a hypothesis, conduct legal research to work toward developing a possible solution, publish our research, apply the legal theory to a client’s real-world situation, analyze the administrative response from the IRS, and then decide whether to litigate, redefine, or withdraw the position.

If the IRS points out something we had previously not considered and the legal position cannot be redefined to cure the issue, then we would withdraw the position and issue a notice to any clients to whom it applied. If, however, the position can be cured by redefining the position, then we will do so assuming the clients’ facts support the redefinition. This would, of course, entail contacting the client to seek clarification. If, however, we do not agree with the IRS response, then we will pursue litigation to seek judicial clarification in our favor.

The Scientific Method helps our tax system mature, develop, and improve by asking new questions and developing new interpretations of our tax code, answering previously unanswered questions, testing these legal theories in the federal judiciary, and eliminating ambiguity through judicial clarification. Judicial clarification even helps eliminate the need of tax attorneys who financially benefit from legal ambiguity. A fair and balanced tax system is one that is clear and concise with zero ambiguity. This can only be achieved through judicial clarification.

In the U.S. legal system, the "strength" of a legal interpretation can be quantified based on the amount of legal support for the interpretation. While a portion of this quantification is certainly subjective based on the reviewer’s legal interpretative philosophy, it is indisputable that a quantified range that encompasses all interpretative philosophies can be established. In some cases, this range can vary wildly. The importance of the level of legal authority is that it determines when penalties will and will not apply as well as when disclosure is and is not required to avoid said penalties. The range of levels of legal confidences are, from weakest to strongest, Reasonable Basis, Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, Should, and Will. In actual practice, a “Will” level opinion is never sought out by taxpayers since that would simply be a reiteration of basic textbook principles of the tax code. Likewise, a “Reasonable Basis” level opinion is rarely issued since, absent a compelling political or social purpose, it is highly unlikely to prevail in court. If, however, the topic of the “Reasonable Basis” opinion implicates a compelling political or social issue, such as the deduction for child care expenses, then our confidence in our ability to sway the federal judiciary increases, and we are, therefore, much more confident in asserting said legal position before the federal judiciary. This leaves only three confidence levels: Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, and Should. These are the three confidence levels within which our firm primarily operates.

A “Substantial Authority” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a 35 percent to 49 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “More Likely Than Not” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a greater than 50 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “Should” opinion, which is the threshold of opinion expressed in this letter, generally means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a chance greater than 70 percent of success on the merits. It is important to note that these quantifications themselves are hotly contested, which implicates “void of vagueness” concerns.

The confidence level of the legal interpretation expressed in this article is: Reasonable Basis.

Bluebook Citation

The Case for Deducting Child Care Expenses, Int’l Tax Online Law Journal (December 30, 2020) url.

Legal Citations

[1] The statutory successor to this provision is Section 262(a) of the Code: “Except as otherwise expressly provided in this chapter [Sections 1 through 1400z-2], no deduction shall be allowed for personal, living, or family expenses.” Unlike the former provision, the modern provision leaves open the possibility of exceptions. It is therefore subordinate to other sections that may permit the deductibility of “personal, living, or family expenses.”

[2] Smith v. Commission, 40 B.T.A. 1038 (1939), aff’d, 113 F.2d 114 (2d Cir. 1940).

[3] Interestingly, Judge Opper cited Burkhart v. Commissioner, a case in which compensation rendered to a wife for domestic services was judicially declared to be “not income” for federal income tax purposes. 11 B.T.A. 275 (1928). Again, for clarification, that case did not only declare that the expense was not deductible to the husband but went further in declaring it was “not income” for the wife. This case actually contradicts Judge Opper’s legal reasoning.

[4] Nammack v. C.I.R., 56 T.C. 1379, 1384 (1971), aff'd sub nom., 459 F.2d 1045 (2d Cir. 1972).

[5] Hubbart v. C.I.R., 4 T.C. 121 (1944); O'Connor v. C.I.R., 6 T.C. 323 (1946); Seese v. C.I.R., 7 T.C. 925 (1946); Wendell v. C.I.R., 12 T.C. 161 (1949); Ochs v. C.I.R., 195 F.2d 692 (2d Cir. 1952); Jackson v. C.I.R., 13 T.C.M. (CCH) 1175 (T.C. 1954); C.I.R. v. Moran, 236 F.2d 595 (8th Cir. 1956); Ingalls v. Patterson, 158 F. Supp. 627 (N.D. Ala. 1958); King v. C.I.R., 19 T.C.M. (CCH) 1519 (T.C. 1960); Levy v. C.I.R., 20 T.C.M. (CCH) 1534 (T.C. 1961); Kroll v. C.I.R., 49 T.C. 557 (1968); Carroll v. C.I.R., 51 T.C. 213 (1968), aff'd sub nom. Carroll v. C.I.R., 418 F.2d 91 (7th Cir. 1969); Drake v. C.I.R., 52 T.C. 842 (1969); International Artists Ltd. v. C.I.R., 55 T.C. 94 (1970); Fred W. Amend Co. v. C.I.R., 55 T.C. 320 (1970), aff'd sub nom. Fred W. Amend Co. v. C.I.R., 454 F.2d 399 (7th Cir. 1971); Simenstad v. U.S., 325 F. Supp. 1249 (N.D. Cal. 1971); Nammack v. C.I.R., 56 T.C. 1379 (1971), aff'd sub nom. Nammack v. C.I.R., 459 F.2d 1045 (2d Cir. 1972); Smail v. C.I.R., 60 T.C. 719 (1973), aff'd sub nom. Smail v. C.I.R., No. 73-1960, 1974 WL 2793 (10th Cir. Oct. 9, 1974); Hanagan v. C.I.R., 33 T.C.M. (CCH) 642 (T.C. 1974); O'Reilly v. C.I.R., 33 T.C.M. (CCH) 1153 (T.C. 1974); Baldwin v. C.I.R., 36 T.C.M. (CCH) 995 (T.C. 1977); Shonkwiler v. C.I.R., 37 T.C.M. (CCH) 546 (T.C. 1978); Green v. C.I.R., 74 T.C. 1229 (1980); Briggs v. C.I.R., 75 T.C. 465 (1980), aff'd, 694 F.2d 614 (9th Cir. 1982); Calarco v. C.I.R., No. 1530-03S, 2004 WL 1616387 (T.C. July 20, 2004); Kuntz v. C.I.R., 101 T.C.M. (CCH) 1239 (T.C. 2011).

[6] T.C. Memo. 2011-52 (T.C. 2011). In this case, a husband had a wife with Alzheimer’s disease. In order to pursue gainful employment, he had to hire a caregiver. The U.S. Tax Court denied the deduction. The taxpayer did not appeal, but only because the expense survived as a deductible medical expense. The court, in a footnote, also pointed out that the taxpayers could have claimed a credit under Section 21, which evidences that the taxpayers were simply not knowledgeable of the law.

[7] Commissioner v. Moran, 236 F.2d 595 (8th Cir. 1956).

[9] Commissioner v. Doak, 234 F.2d 704 (4th Cir. 1956).

[10] N. Tr. Co. v. Campbell, 211 F.2d 251, 253 (7th Cir. 1954).