Background

26 U.S.C. § 6664(c)(1) states “No penalty shall be imposed under section 6662 or 6663 with respect to any portion of an underpayment if it is shown that there was a reasonable cause for such portion and that the taxpayer acted in good faith with respect to such portion.” Congress enacted Section 6664(c)(1) to codify the Reasonable Cause Exception. Basically, if a taxpayer acted in good-faith and there was a situation that reasonably caused an issue, then penalties should not apply.

A question that sometimes arises is whether a person is suffering from addiction suffers from such incapacitation as to warrant reasonable cause. This article will thoroughly dissect all of the relevant cases that have expressed opinions on the matter.

The Kantor Case

One of the first cases to very substantively analyze this issue was the 1995 case of Kantor v. Commissioner.[1] In that case, the Tax Court found the following:

“Evidence of emotional or substance abuse problems can rebut evidence of fraudulent intent, either by showing that it prevented the taxpayer from forming the requisite intent, Hollman v. Commissioner, 38 T.C. 251, 259-260 (1962) (“considerable psychiatric evidence” of a severe psychosis overcame other evidence showing taxpayer’s “astuteness and awareness of matters” and participation in “intricate financial operations during the tax years”), supplemented by T.C. Memo. 1962-236, or as part of a larger pattern of facts and circumstances that does not present clear and convincing evidence to the court. Gutierrez v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1995-252 (combination of alcoholism, lax record-keeping, and cooperation with IRS indicated lack of fraudulent intent), aff’d. in part and rev’d. and remanded on other issues without published opinion 105 F.3d 651 (5th Cir. 1996).”[2]

The Kantor Court went on to find:

“In other cases, this Court has used the presence of compelling evidence of a taxpayer’s acts to mislead and conceal to find fraud, despite evidence of mental illness, Yarbrough Oldsmobile Cadillac, Inc. v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1995-538 (brain tumor did not prevent finding of fraud when other indicia such as falsified records, disallowed deductions, use of a corporation to disguise personal expenses as business expenses proved fraud), or drug use-- even drug addiction; see Maniloff v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1991-554 (testimony of extensive drug use insufficient to rebut other evidence showing participation in fraudulent and illegal activities); Yocum v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1985-447 (drug addiction insufficient to rebut fraudulent intent of taxpayer who engaged in drug smuggling); Chaffin v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo. 1983-394 (drinking problem did not preclude forming fraudulent intent).”[3]

Ultimately, the Kantor Court found that the taxpayer’s argument failed because he “presented no psychiatric testimony or other evidence of mental impairment caused by drug addiction that prevented [him] from forming the requisite intent.”[4]

The Kantor case reveals the importance of scientific and medical evidence. Without expert testimony evidencing the effect the substance abuse had and how it contributed to underpayment, a court will likely reject the claim, especially when the taxpayer was not cooperative, highly educated, financially sophisticated, and was aware of his tax reporting obligations.

The Watts Case

The Watts case dealt with taxpayer who claimed mental incapacitation resulting from severe distress due to his mother’s illness.[5] In that case, the Tax Court agreed that illness of a family member can qualify as reasonable cause, but the court also found that the “taxpayer’s selective inability to perform his or her tax obligations, while performing their regular business, does not excuse failure to file.”[6]

The problem in the Watts case, similar to the Kantor case, was a lack of expert testimony explaining the seemingly selective inability to comply with tax obligations while conducting regular business activities.

Had Robert and Diana Watts retained expert psychiatric witnesses to testify that one’s work is often used as an escape from the trauma resulting from the loss of a mother, the Court could have been convinced that this was not a case of selective incapacitation but rather someone who simply escaped the trauma of reality by drowning themselves in work. Like the Kantor case, it highlights the needs for expert medical testimony.

The Jordan Case

In 2005, the Tax Court revisited the issue in Jordan v. Commissioner.[7] In that case, the Tax Court made it clear that “the sole issue for decision is whether petitioner's drug addiction for which he underwent approximately 3 weeks of rehabilitation… coupled with his other medical problems and related memory loss, gave him reasonable cause.”[8]

In that case, the taxpayer was medically prescribed OxyContin and became addicted to it. After he stopped taking it, he had a seizure and suffered memory loss. After the seizure, he attended a 3-week rehabilitation program.

The Court found that although the taxpayer had “introduced evidence regarding his heart problems, his headaches, and his drug addiction and rehabilitation,” they did not believe that it “incapacitated him to such an extent that he was unable to file his returns.” In support of this, they cited Ramirez v. Commissioner[9] to draw an analogy to the fact that the taxpayer continued to operate his business without issue. In fact, they emphasized that the tax years in question were his highest revenue-generating years of his company’s history. The business’s invoices and expenses were all paid without issue. They then referenced “selective incapacity” and cited to Wright v. Commissioner,[10] which was similar to the Watts case.

Again, the issue here is that the taxpayer in Jordan failed to introduce expert medical testimony to explain the selective incapacitation. A medical professional would know that drugs can have the effect of re-wiring a victim’s brain to do anything and everything necessary to generate revenue to continue fueling the addiction. As such, you will see high-performing addicts continue to efficiently operate their businesses because that is the source of funding for the addiction. However, this means nothing coming from a non-medical professional. But if it comes from someone with a Harvard medical degree (an expert medical witness), you can see how the court could be swayed.

The Thomas Case

In Thomas v. Commissioner, the Tax Court concluded that “bilateral tendinitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and periods of depression” were insufficient to constitute reasonable cause.[11] This was simply a weak case on the facts, and the taxpayer did not introduce any expert testimony.

The Jones Case

In Jones v. Commissioner, the Tax Court explained that when “a taxpayer's disability is raised as part of a reasonable cause defense, [they] have looked to the severity of the disability and the impact it had on the taxpayer's life, explaining that “significant psychiatric disorder and [mental incapacitation] during the period under consideration” or confinement to various hospitals for “severe mental illness,” may provide reasonable cause.”[12]

Nevertheless, the Court concluded because the taxpayer was only “diagnosed with an illness which involved mental distress,” his health problems did not constitute reasonable cause.

Again, there was no expert medical testimony explaining how the illness that involved mental distress contributed to the noncompliance.

The Hazel Case

In the 2008 case of Hazel v. Commissioner, the Tax Court was confronted with a taxpayer who had a “long history of alcoholism and drug addiction.”[13] The Court also found the taxpayer’s “testimony that he suffered from a long history of alcohol and drug abuse credible.” Nevertheless, the Court concluded that the testimony was “contradictory, general, conclusory, and self-serving.” This again highlights the absolute necessity of having an expert medical witness, which the Court made expressly clear when they elaborated and explained that “[u]nder the circumstances, we are not required to accept his testimony, and we do not.” The Hazel Court basically said the taxpayer was credible, but they were still rejecting his testimony because medical explanations should be given by an expert medical witness; that’s the only way to bind the Court.

The Hazel case again illustrated the absolute necessity of expert medical and psychiatric witnesses to explain in precise detail how the substance abuse resulted in noncompliance. Without expert witnesses, a court will reject the testimony of a taxpayer even if they conclude he is credible.

The Remisovsky Case

The 2022 case of Remisovsky v. Commissioner is incredibly important because it cites to and analyzes the Jones, Thomas, Hazel, andWatts cases and is the most recent substance abuse case before the U.S. Tax Court.[14] The Court found that the taxpayer “offered generalized testimony that he had struggled with depression and alcoholism. But at trial he supplied no testimony that he suffered from these conditions at the relevant times.” As such, this case was lost entirely based on inadequate defense and preparation. Nevertheless, it highlighted and confirmed all of the concerns expressed in this article.

Conclusion

If a taxpayer is relying on substance abuse to explain noncompliance with tax obligations, the major hurdle will be to explain what the court will view as “selective incapacity.”[15] In other words, a taxpayer will have to explain why he was too incapacitated to file or pay his taxes but not incapacitated to conduct business affairs.

This cannot be done by the taxpayer or a lay witness. It can only be established by a qualified and licensed medical professional. A psychiatrist or medical doctor with impeccable credentials. This expert witness must be retained to provide expert testimony to the court to explain the effect of the substance abuse on the brain. If the taxpayer continued conducting business affairs, only an expert medical witness would be able to explain what the courts have largely labeled as “selective incapacitation.”

Legal Disclosure

This article is not intended to be relied on for the purpose of establishing reasonable cause, good faith, or avoiding tax-related penalties under the Internal Revenue Code. The requirements for written legal advice to establish reasonable cause for the avoidance of penalties are outlined in 31 C.F.R. § 10.37. It is improper and impermissible to rely on this article as legal advice. In the U.S. tax system, generally, only a paid consultation or formal written tax opinion can be used as an affirmative defense to penalties. Free consultations may not be relied upon as legal advice for the purpose of avoiding penalties. The objective of a free consultation is to determine the client’s issue, fact pattern, and whether the firm can provide a legally viable solution with a minimum of Substantial Authority to support it. If you require formal legal advice upon which you can legally rely to establish reasonable cause, please contact our firm.

Confidence Level Disclosure

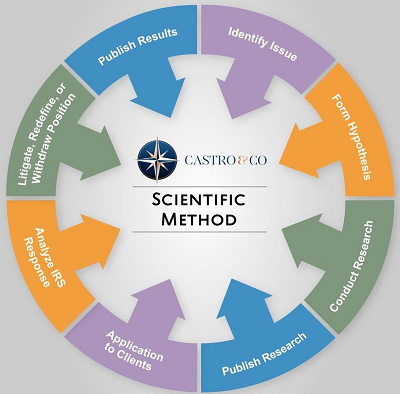

For over 3600 years, the scientific method has been used by innovative individuals as an empirical method of acquiring knowledge. In the world of tax law, it is no different. In some cases, we offer free consultations to identify the issue, form a hypothesis, conduct legal research to work toward developing a possible solution, publish our research, apply the legal theory to a client’s real-world situation, analyze the administrative response from the IRS, and then decide whether to litigate, redefine, or withdraw the position.

If the IRS points out something we had previously not considered and the legal position cannot be redefined to cure the issue, then we would withdraw the position and issue a notice to any clients to whom it applied. If, however, the position can be cured by redefining the position, then we will do so assuming the clients’ facts support the redefinition. This would, of course, entail contacting the client to seek clarification. If, however, we do not agree with the IRS response, then we will pursue litigation to seek judicial clarification in our favor.

The Scientific Method helps our tax system mature, develop, and improve by asking new questions and developing new interpretations of our tax code, answering previously unanswered questions, testing these legal theories in the federal judiciary, and eliminating ambiguity through judicial clarification. Judicial clarification even helps eliminate the need of tax attorneys who financially benefit from legal ambiguity. A fair and balanced tax system is one that is clear and concise with zero ambiguity. This can only be achieved through judicial clarification.

In the U.S. legal system, the "strength" of a legal interpretation can be quantified based on the amount of legal support for the interpretation. While a portion of this quantification is certainly subjective based on the reviewer’s legal interpretative philosophy, it is indisputable that a quantified range that encompasses all interpretative philosophies can be established. In some cases, this range can vary wildly. The importance of the level of legal authority is that it determines when penalties will and will not apply as well as when disclosure is and is not required to avoid said penalties. The range of levels of legal confidences are, from weakest to strongest, Reasonable Basis, Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, Should, and Will. In actual practice, a “Will” level opinion is never sought out by taxpayers since that would simply be a reiteration of basic textbook principles of the tax code. Likewise, a “Reasonable Basis” level opinion is rarely issued since, absent a compelling political or social purpose, it is highly unlikely to prevail in court. If, however, the topic of the “Reasonable Basis” opinion implicates a compelling political or social issue, such as the deduction for child care expenses, then our confidence in our ability to sway the federal judiciary increases, and we are, therefore, much more confident in asserting said legal position before the federal judiciary. This leaves only three confidence levels: Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, and Should. These are the three confidence levels within which our firm primarily operates.

A “Substantial Authority” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a 35 percent to 49 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “More Likely Than Not” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a greater than 50 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “Should” opinion, which is the threshold of opinion expressed in this letter, generally means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a chance greater than 70 percent of success on the merits. It is important to note that these quantifications themselves are hotly contested, which implicates “void of vagueness” concerns.

Bluebook Citation

Drug Use May Constitute Reasonable Cause, Int’l Tax Online Law Journal (December 13, 2023) url.

Legal Citations

[1] See No. 20429-93, 1997 WL 93309, at *1 (T.C. Mar. 5, 1997).

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Kantor at *7.

[5] Watts v. Commissioner, No. 9289-98, 1999 WL 1247548, at *2 (T.C. Dec. 23, 1999).

[6] Id.

[7] See No. 13351-04, 2005 WL 3081646, at *1 (T.C. Nov. 17, 2005).

[8] Id.

[9] Ramirez v. Commissioner, No. 22323-03L, 2005 WL 1693679 (T.C. July 21, 2005)

[10] See Wright v. Commissioner, No. 273-96, 1998 WL 331470 (T.C. June 24, 1998), aff’d, 173 F.3d 848 (2d Cir. 1999).

[11] Thomas v. Commissioner, No. 10824-03, 2005 WL 2860497, at *3 (T.C. Nov. 1, 2005).

[12] Jones v. Commissioner, No. 14608-04, 2006 WL 2423425, at *6 (T.C. Aug. 22, 2006) (citing Shaffer v. Commissioner, No. 23525-92, 1994 WL 704767 (T.C. Dec. 19, 1994)) (citing Carnahan v. Commissioner, No. 12621-92, 1994 WL 135342 (T.C. Apr. 18, 1994), aff'd, 70 F.3d 637 (D.C. Cir. 1995)).

[13] No. 23558-06, 2008 WL 2095614, at *1 (T.C. May 19, 2008).

[14] See No. 11945-20L, 2022 WL 3755390, at *3 (T.C. Aug. 30, 2022).

[15] U.S. v. Boyle, 1985-1 C.B. 372, 469 U.S. 241, 105 S. Ct. 687, 83 L. Ed. 2d 622, Unempl. Ins. Rep. (CCH) P 16388, 85-1 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P 13602, 55 A.F.T.R.2d 85-1535 (1985); Pinkham v. C. I. R., T.C. Memo. 1958-216, T.C.M. (P-H) P 58216, 17 T.C.M. (CCH) 1071, 1958 WL 863 (T.C. 1958). This rule was also recognized in Williams v. C.I.R., 16 T.C. 893, 1951 WL 137 (T.C. 1951). See Tamberella v. C.I.R., T.C. Memo. 2004-47, T.C.M. (RIA) P 2004-047, 87 T.C.M. (CCH) 1020 (2004), aff'd, 139 Fed. Appx. 319, 2005-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) P 50487, 96 A.F.T.R.2d 2005-5311 (2d Cir. 2005); McLaine v. C.I.R., 138 T.C. 228, Tax Ct. Rep. (CCH) 58977, Tax Ct. Rep. Dec. (RIA) 138.10, 2012 WL 833227 (2012), as amended, (June 7, 2012); Hardin v. C.I.R., T.C. Memo. 2012-162, T.C.M. (RIA) P 2012-162, 103 T.C.M. (CCH) 1861 (2012); Ruggeri v. C.I.R., T.C. Memo. 2008-300, T.C.M. (RIA) P 2008-300, 96 T.C.M. (CCH) 511 (2008).