Income and gains within a Singapore CPF are exempt from U.S. tax during the growth phase prior to retirement pursuant to domestic U.S. tax law that views it as foreign social security, which is taxed in the same manner as a tax-deferred annuity if and only if there is adequate disclosure on your U.S. federal income tax return. In other words, there is no tax until the Singaporean Central Provident Fund annuitizes at retirement and begins paying benefits.

Contact our firm today to schedule a free consultation by clicking here to submit your information online and be contacted by our firm. We can handle the preparation and submission of your U.S. federal income tax return to ensure your Singaporean Central Provident Fund is not exposed to U.S. income tax.

The Singaporean Social Security System

The U.S. Social Security Administration’s 2010 publication titled “Social Security Programs Throughout the World” analyzes Singapore’s overall comprehensive social security system. The first of laws implementing social security in Singapore were enacted in 1953.

Singapore’s current social security system is based on the Central Provident Fund Act of 2001 with amendments from 2002 to 2017, and the Silver Support Scheme Act of 2015. These laws are all similar to compulsory contributions under the U.S. Federal Insurance Contributions Act.[1] The two programs are the Provident Fund and the Social Assistance Silver Support Scheme. The Provident Fund system covers employed persons, including most categories of public-sector employees and self-employed persons with annual net income greater than S$6,000 (MA only). There is voluntary coverage for persons without mandatory coverage. There is also a special system for certain categories of public-sector employees, including administrative service staff.. The Silver Support Scheme system covers the poor and elderly citizens of Singapore.

The Central Provident Fund (CPF) provides four types of individual accounts for each member: an Ordinary Account (OA) to finance the purchase of a home, approved investments, life and mortgage insurance, and education; a Special Account (SA), principally for retirement (may invest in retirement-related financial products); a MediSave account (MA) for certain hospitalization and medical expenses (see Sickness and Maternity); and a Retirement Account (RA) set up at age 55 to finance monthly payments at retirement.

Singaporean Central Provident Funds can most aptly be characterized as state-managed retirement savings scheme with the primary purpose of providing for income at retirement, and it is specifically recognized as social security by the U.S. Social Security Administration.[2] Moreover, a state-mandated “occupational pension scheme” fits the precise definition of social security according to the OECD.[3] Furthermore, the International Social Security Association, of which Singapore and the United States are members, also recognizes Singaporean Central Provident Funds as forming part of Singapore’s overall comprehensive social security system.[4]

Therefore, based on the foregoing substantial and compelling authorities, it is indisputable that Singaporean Central Provident Funds are social security accounts forming a part of Singapore’s overall comprehensive social security system.

* We are aware that other international tax professionals have made the bizarre claim that if a foreign social security system is not identical to the U.S. social security system, it cannot qualify as social security. That is simply not how international law works. Each country is free to structure and design their own social security systems how they like. Under international conflict of law principles, if a foreign system is considered social security under international law, that characterization is binding upon U.S. law.

International Social Security Law

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (“OECD”), the term “social security” generally “refers to a system of mandatory protection that a State puts in place in order to provide its population with… retirement benefits.”[5] The OECD commentary broadly interprets “payments under a social security system” to include payments under a “worker’s compensation fund,” which is not considered “social security” in the United States, which is proof that the United States’ definition of “social security” is not the controlling factor.

If both the U.S. and another country are members of the OECD, U.S. courts will generally defer to OECD commentary to determine the prevailing international interpretation of terms, which is published every few years.[6] The United States joined the OECD in 1961 while Singapore never joined. Therefore, although U.S. courts are not legally bound to defer to the OECD with regard to the definition of social security, the OECD interpretation will weigh heavily of a U.S. federal court’s legal analysis since it promotes international consistency.

Therefore, the OECD takes a very broad and inclusive approach as to what constitutes “social security” under international treaty law, which a U.S. federal court should defer to.

U.S.Tax Treatment of Social Security Payments

Under domestic U.S. tax law, with regard to informational reporting requirements for contributions to a nonqualified deferred compensation plan, Congress specifically exempted contributions to a foreign social security account.[7] This clearly evidences Congressional intent to disregard contributions to foreign social security for U.S. informational reporting purposes on IRS Form 3520 and 3520-A.[8] Moreover, the IRS has specifically stated that, under domestic U.S. tax law, “foreign social security benefits… are taxable as annuities.”[9] Gains within annuities are tax-deferred until the contract annuitizes and payments begin or when the owner cashes out the annuity and takes a lump sum.[10]

Although some practitioners have asserted that Singaporean Central Provident Funds are reportable as foreign grantor trusts on IRS Forms 3520 and 3520-A, doing so would subject the gains within the fund to immediate U.S. taxation, which is contrary to IRS guidance.[11] Some practitioners have also cited a 1997 IRS Memorandum as evidence of the IRS’s position that growth within the Singapore CPF is subject to U.S. tax, but the IRS cannot make law through memoranda.[12] This is why having an assertive tax attorney willing to advocate for you is important. You need a tax attorney that’s willing to and capable of challenging the IRS to change their position. Our firm has successfully convinced the IRS in the past that their position was incorrect.

Conclusion

During the pre-retirement growth phase, income and gains within a Singaporean Central Provident Fund in Singapore are exempt from U.S. tax pursuant to domestic U.S. tax law that views it as foreign social security, which is taxed in the same manner as a tax-deferred annuity if and only if there is adequate disclosure on your U.S. federal income tax return. In other words, there is no tax until the Singaporean Central Provident Fund annuitizes at retirement and begins paying benefits.

Contact Our Firm

Contact our firm today to schedule a free consultation by clicking here to submit your information online and be contacted by our firm. We can handle the preparation and submission of your U.S. federal income tax return to ensure your Singaporean Central Provident Fund is not exposed to U.S. income tax.

Legal Disclosure

This article is not intended to be relied on for the purpose of establishing reasonable cause, good faith, or avoiding tax-related penalties under the Internal Revenue Code. The requirements for written legal advice to establish reasonable cause for the avoidance of penalties are outlined in 31 C.F.R. § 10.37. It is improper and impermissible to rely on this article as legal advice. In the U.S. tax system, generally, only a paid consultation or formal written tax opinion can be used as an affirmative defense to penalties. Free consultations may not be relied upon as legal advice for the purpose of avoiding penalties. The objective of a free consultation is to determine the client’s issue, fact pattern, and whether the firm can provide a legally viable solution with a minimum of Substantial Authority to support it. If you require formal legal advice upon which you can legally rely to establish reasonable cause, please contact our firm.

Confidence Level Disclosure

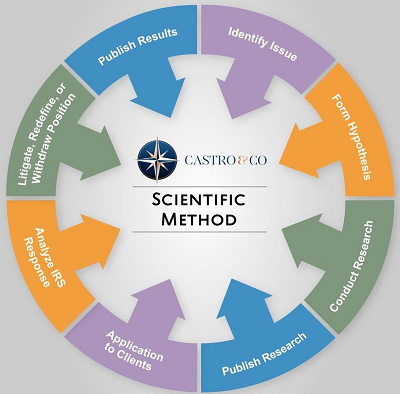

For over 3600 years, the scientific method has been used by innovative individuals as an empirical method of acquiring knowledge. In the world of tax law, it is no different. In some cases, we offer free consultations to identify the issue, form a hypothesis, conduct legal research to work toward developing a possible solution, publish our research, apply the legal theory to a client’s real-world situation, analyze the administrative response from the IRS, and then decide whether to litigate, redefine, or withdraw the position.

If the IRS points out something we had previously not considered and the legal position cannot be redefined to cure the issue, then we would withdraw the position and issue a notice to any clients to whom it applied. If, however, the position can be cured by redefining the position, then we will do so assuming the clients’ facts support the redefinition. This would, of course, entail contacting the client to seek clarification. If, however, we do not agree with the IRS response, then we will pursue litigation to seek judicial clarification in our favor.

The Scientific Method helps our tax system mature, develop, and improve by asking new questions and developing new interpretations of our tax code, answering previously unanswered questions, testing these legal theories in the federal judiciary, and eliminating ambiguity through judicial clarification. Judicial clarification even helps eliminate the need of tax attorneys who financially benefit from legal ambiguity. A fair and balanced tax system is one that is clear and concise with zero ambiguity. This can only be achieved through judicial clarification.

In the U.S. legal system, the "strength" of a legal interpretation can be quantified based on the amount of legal support for the interpretation. While a portion of this quantification is certainly subjective based on the reviewer’s legal interpretative philosophy, it is indisputable that a quantified range that encompasses all interpretative philosophies can be established. In some cases, this range can vary wildly. The importance of the level of legal authority is that it determines when penalties will and will not apply as well as when disclosure is and is not required to avoid said penalties. The range of levels of legal confidences are, from weakest to strongest, Reasonable Basis, Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, Should, and Will. In actual practice, a “Will” level opinion is never sought out by taxpayers since that would simply be a reiteration of basic textbook principles of the tax code. Likewise, a “Reasonable Basis” level opinion is rarely issued since, absent a compelling political or social purpose, it is highly unlikely to prevail in court. If, however, the topic of the “Reasonable Basis” opinion implicates a compelling political or social issue, such as the deduction for child care expenses, then our confidence in our ability to sway the federal judiciary increases, and we are, therefore, much more confident in asserting said legal position before the federal judiciary. This leaves only three confidence levels: Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, and Should. These are the three confidence levels within which our firm primarily operates.

A “Substantial Authority” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a 35 percent to 49 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “More Likely Than Not” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a greater than 50 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “Should” opinion, which is the threshold of opinion expressed in this letter, generally means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a chance greater than 70 percent of success on the merits. It is important to note that these quantifications themselves are hotly contested, which implicates “void of vagueness” concerns.

The confidence level of the legal interpretation expressed in this article is: Should.

Bluebook Citation

Bluebook Citation: U.S. Tax Treatment of Singaporean Central Provident Funds, Castro Int’l Tax Blog (Dec. 8, 2019) url.

[1] See IRC §§ 3101, 3111.

[2] See Social Programs Throughout the World, U.S. Social Security Administration’s Office of Retirement and Disability Policy; also see Individual Accounts in Other Countries, U.S. Social Security Administration’s Office of Policy, http://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v66n1/v66n1p31.html (Sep. 1, 2015).

[3] See 2014 OECD Commentary, Art. 18, ¶ 10.

[4] See Social Security Country Profiles, International Social Security Association, https://www.issa.int/countrydetails?countryId=SG®ionId=ASI.

[5] See 2014 OECD Commentary, Art. 18, ¶ 28.

[6] See Podd v. C.I.R., 76 T.C.M. 906 (1998) (citing U.S. v. A.L. Burbank & Co., 525 F.2d 9, 15 (2d Cir. 1975); North W. Life Assurance Co. of Canada v. C.I.R., 107 T.C. 363 (1996); Taisei Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. C.I.R., 104 T.C. 535, 546 (1995) (construing the Convention for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income, Mar. 8, 1971, U.S.-Japan, 23 U.S.T. 969, with reference to the Model Treaty and its commentary)).

[7] See Treas. Reg. § 1.409A-1(a)(3)(iv).

[8] See Dominion Res., Inc. v. U.S., 681 F.3d 1313 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (Treasury cannot interfere with the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress).

[9] See IRS Publication 17, Page 84; also see The International Tax Gap Series, “Most income tax treaties have special rules for social security payments. In many cases, foreign social security payments are taxable by the country making the payments. Unless specified otherwise in an income tax treaty, foreign social security pensions are generally taxed as if they were foreign pensions or foreign annuities. Unless a tax treaty allows it (see, e.g., the USA-Canada treaty), they are not eligible for exclusion from taxable income the way a U.S. social security pension might be.” https://www.irs.gov/businesses/the-taxation-of-foreign-pension-and-annuity-distributions

[10] See IRC § 72.

[11] If Singaporean Central Provident Funds were foreign private company-sponsored pension plans, they would certainly be subject to reporting on IRS Forms 3520 and 3520-A. However, being social security, they are not subject to reporting since they constitute foreign social security, which is taxable in the same manner as an annuity in accordance with IRS Publication 17.

[12] IRS Memorandum (Oct. 10, 1997), https://www.irs.gov/pub/lanoa/pmta00173_6973.pdf.