A question that often comes up with clients reviewing their 2018 and 2019 tax returns is: what in the world are temporary work-related impairment expenses? Referred to in tax year 2020 as "Work-Connected Impairment Prevention Expenses," to be defined below, are legally deductible pursuant to three separate and distinct sections of the Internal Revenue Code: 67(b)(6)/(d)(1)-(2), 162, and 212.

This article will exclusively analyze the deductibility of these expenses under Code section 67. A separate article will discuss their deductibility under Code section 162 and 212. It is important to note that tax year 2020 was the last year we recommended this legal position for two reasons: (1) we want to give the IRS the opportunity to challenge our interpretation and application of this deduction, and (2) we no longer recommend legal positions with less than Substantial Authority unless the legal position promotes a substantial social objective.

Deductibility Under Section 67(b)(6), (d)(1)-(2)

Code section 67(b)(6) reads “For purposes of this section, the term “miscellaneous itemized deductions” means the itemized deductions other than any deduction allowable for impairment-related work expenses.” In other words, impairment expenses are not considered a miscellaneous deduction subject to the 2% floor for deductibility.

There are three requirements to claim a deduction under Code section 67(b)(6):

- The individual at issue must be a “handicapped individual as defined in section 190(b)(3),” which we’ll call the “Qualifying Individual” Requirement to avoid confusion;

- The expenses are in connection with the individual’s place of employment which are necessary for such individual to be able to work, which we’ll call the “Work Connection” Requirement, and

- If this section did not exist, the expense would still qualify as deductible under section 162, which we’ll call the “Ordinary and Necessary” Requirement.

Qualifying Individual

In analyzing the first requirement, it is critical to look beyond the ordinary use of the term “handicapped individual” since the statute directly references and defers to an existing statutory provision for the definition, which could be much more broad than the ordinary use of the term or much more restrictive.

As mentioned above, Code section 67(d)(1) specifically refers to “a handicapped individual as defined in section 190(b)(3).” In other words, we refer to Code section 190 for the sole and limited purpose of determining the definition of a “handicapped individual” under Code section 190(b)(3). No other provision of Code section 190 is relevant for the purpose of this matter.

Under Code section 190(b)(3), “the term handicapped individual means any individual who has a physical... disability… which for such individual constitutes… a functional limitation to employment, or who has any physical... impairment… which substantially limits one or more major life activities of such individual.”

In other words, there are two avenues to claiming to be a qualifying individual.

Avenue One requires the individual to have a physical “disability” which “for such individual constitutes” a “functional limitation to employment.”

Avenue Two requires the individual to have a physical “impairment” which “substantially limits” a “major life activity.”

The statute does not define “disability,” the seemingly highly subjective “for such individual” standard, the critical “impairment” term, or the standard for whether the impairment “substantially limits” activities.

For clarification and gap-filling, we are supposed to rely on Treasury Regulations. However, Treas. Reg. § 1.190-2(a)(3) simply reiterates the statute: “The term ‘handicapped individual’ means any individual who has a physical... disability... which for such individual constitutes... a functional limitation to employment, or a physical... impairment... which substantially limits one or more of such individual's major life activities, such as performing manual tasks, walking, speaking, breathing, learning, or working.” This is either a gross dereliction of duty on the part of the Treasury to provide guidance or intentional Strategic Ambiguity. Which is it? Is Treasury incompetent in failing to provide real guidance or nefarious by intentionally keeping the law unconstitutionally vague?

Moreover, Treasury regulations do not provide any additional clarification or guidance other than providing examples of what major life activity entails. The regulations do not clarify critical terms and matters such as:

- What constitutes an “impairment”?

- What constitutes a “functional limitation”?

- How subjective is the “for such individual constitutes… a functional limitation” standard?

- How does one determine whether such impairment “substantially limits” a major life activity?

Because Treasury has not promulgated regulations limiting the interpretation of impairment expenses in order to obtain the benefit of deference with regard to statutory interpretation, which is known as Chevron deference based on the U.S. Supreme Court case that afforded executive agencies judicial deference with regard to interpreting statutes affecting the laws they’re tasked with enforcing within certain limits, the legal community is free to interpret this provision as broadly as one deems to be reasonable.

For example, strep throat substantially limits one’s ability to speak. According to regulations promulgated under Section 190(b)(3), "speaking" is specifically listed as a "major life activity." Therefore, an individual that has strep throat would meet the definition of a "handicapped individual" under Section 190(b)(3). In other words, strep throat is a qualifying impairment since it results in a functional limitation to a major life activity thus allowing the individual to be deemed to be a qualifying individual. Ridiculous? Not as ridiculous as Treasury's incompetence in failing to do its job for the past 40 years. If Treasury would actually do its job and promulgate a proper regulation, they would not have to deal with this.

This is why promulgating regulations to interpret statutes is a critical task for the U.S. Department of the Treasury. Without Treasury regulations, any reasonable interpretation of the statute will be upheld by the courts. Treasury regulations are specifically designed to limit creative tax planning and lawyering with regard to statutory interpretation.

Work Connection

Code section 67(b)(6) requires the expenses to be “in connection with” the workplace and “necessary for such individual to be able to work.”

Again, Treasury regulations do not provide guidance, and there is absolutely no case law on this topic since the provision was enacted in 1986. Not a single court case in nearly 40 years. * Where the law is ambiguous and case authority is sparse and arguably supports the position, good faith will be assumed. Rueckert v. Gore, 587 F. Supp. 1238 (N.D. Ill. 1984), aff'd sub nom. Rueckert v. IRS, 775 F.2d 208 (7th Cir. 1985).

Preventive health care has long been viewed as being necessary for employees to work without concern of contracting contagions or infecting coworkers with contagious illnesses.

According to a report titled “Promoting Prevention Through the Affordable Care Act: Workplace Wellness” published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, “declining workforce health contributes to an increase in health-related expenses, both in direct medical payments and indirect costs resulting from absenteeism and presenteeism. [Preventive] Wellness programs have been shown to save money; however, such programs are underused. One reason may be that the future benefits of healthy employees are significantly undervalued relative to the cost.” In other words, preventive health expenses, by virtue of their ability to reduce sick day claims and the spread of contagious illnesses in the workplace, are necessary for individuals to work with less *interruption, which increases workplace productivity.

Ordinary and Necessary

Code section 162 is abundantly clear with regard to the deductibility of any expenses that are inextricably linked to the production of income, including expenses associated with one’s health, such as medical expenses, health insurance, long-term care services, long-term care premiums of working individuals. * A prior version of this article appears to have suggested medical expenses of the entire family were deductible and that is incorrect; only for working individuals.

Statutory Overlapping

While this certainly creates overlap with Code section 213’s deduction for medical expenses, it is an overlap caused by Congress’s inability to pass laws that are clear and explicit, Treasury’s inability to promulgate regulations interpreting this provision, and the judiciary’s lack of interpretive guidance largely due to the IRS’s unwillingness to challenge firms like ours on this matter for fear of “opening the flood gates” on a new deduction.

Conclusion

Unless and until either the U.S. Treasury promulgates regulations or the judiciary provides clarifying guidance or a definitive interpretation of this statutory provision, the most reasonably broad interpretation of Code section 67(d)(1) is as follows:

The term “impairment-related work expenses” means expenses directly related to curing or preventing a functional limitation that, if contracted, would either result in a substantial limitation to an individual’s ability to perform job functions or pose a risk to others at his or her place of employment.

In other words, after the passage of the Affordable Care Act, our firm began deducting all medical expenses as impairment expenses in light of the new national policy that preventive healthcare was necessary to a workplace.

Contact Our Firm

Contact our firm today to schedule a free consultation by clicking here to submit your information online and be contacted by our firm.

Legal Disclosure

This article is not legal advice. It is improper to rely on this article as legal advice. In the U.S. tax system, generally, only a paid consultation or formal written tax opinion can be used as an affirmative defense to penalties. Free consultations may not be relied upon as legal advice for the purpose of avoiding penalties. The objective of a free consultation is to determine the client’s issue, fact pattern, and whether the firm can provide a legally viable solution with a minimum of Substantial Authority to support it.

Confidence Level Disclosure

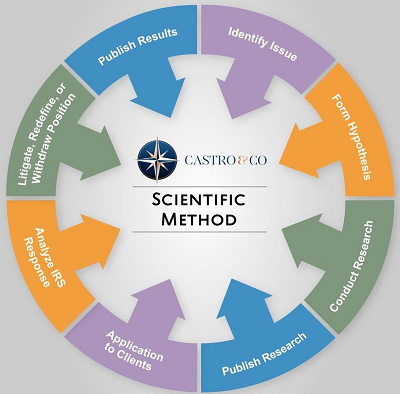

For over 3600 years, the scientific method has been used by innovative individuals as an empirical method of acquiring knowledge. In the world of tax law, it is no different. In some cases, we offer free consultations to identify the issue, form a hypothesis, conduct legal research to work toward developing a possible solution, publish our research, apply the legal theory to a client’s real-world situation, analyze the administrative response from the IRS, and then decide whether to litigate, redefine, or withdraw the position.

If the IRS points out something we had previously not considered and the legal position cannot be redefined to cure the issue, then we would withdraw the position and issue a notice to any clients to whom it applied. If, however, the position can be cured by redefining the position, then we will do so assuming the clients’ facts support the redefinition. This would, of course, entail contacting the client to seek clarification. If, however, we do not agree with the IRS response, then we will pursue litigation to seek judicial clarification in our favor.

The Scientific Method helps our tax system mature, develop, and improve by asking new questions and developing new interpretations of our tax code, answering previously unanswered questions, testing these legal theories in the federal judiciary, and eliminating ambiguity through judicial clarification. Judicial clarification even helps eliminate the need of tax attorneys who financially benefit from legal ambiguity. Our fair and balanced tax system is one that is clear and concise with zero ambiguity. This can only be achieved through judicial clarification.

In the U.S. legal system, legal interpretations can be quantified based on the amount of legal support for it. While a portion of this quantification is subjective based on the reviewer’s legal interpretative philosophy, it is indisputable that a quantified range that encompasses all interpretative philosophies can be established. The importance of the level of legal authority is that it determines when penalties will and will not apply as well as when disclosure is and is not required to avoid said penalties. The range of levels of legal confidences are, from weakest to strongest, Reasonable Basis, Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, Should, and Will. In actual practice, a “Will” level opinion is never sought out by taxpayers since that would simply be a reiteration of basic textbook principles of the tax code. Likewise, a “Reasonable Basis” level opinion is rarely issued since, absent a compelling political or social purpose, it is highly unlikely to prevail in court. If, however, the topic of the “Reasonable Basis” opinion implicates a compelling political or social issue, such as the deduction for child care expenses, then our confidence in our ability to sway the federal judiciary increases, and we are, therefore, much more confident in asserting said legal position before the federal judiciary. This leaves only three confidence levels: Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, and Should. These are the three confidence levels within which our firm primarily operates.

A “Substantial Authority” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a 35 percent to 49 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “More Likely Than Not” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a greater than 50 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “Should” opinion, which is the threshold of opinion expressed in this letter, generally means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a chance greater than 70 percent of success on the merits. It is important to note that these quantifications themselves are hotly contested, which implicates “void of vagueness” concerns.

The confidence level of the legal interpretation expressed in this article is: Substantial Authority.

Bluebook Citation

Work-Related Temporary Impairment Expenses, Castro Int’l Tax Blog (June 27, 2018) url.