UPDATE: 06/14/2022

We have secured a legal opinion from Terence "Terry" Dwyer of Dwyer Lawyers in Australia confirming that wages earned by Americans at JDFPG are exempt from Australian income taxation under domestic Australian tax law. Read the opinion by clicking here.

UPDATE: 03/25/2022

Under Section 6103(b)(2)(D), a Closing Agreement is considered confidential tax "return information" that the IRS is not permitted to disclose to any third-parties; let alone outsource the collection of to an employer or a third-party accounting firm. The IRS has basically admitted to a systematic violation of JDFPG taxpayers' privacy rights under Section 6103.

UPDATE: 02/11/2020

Our firm recently discovered ATO Taxation Ruling 2005-008. In this ruling, the ATO indisputably agrees with our firm's interpretation of Article 19. This is monumental because Alison Lendon, ATO Deputy Commissioner of Taxation, and John Wynter, low-level examiner, have been asserting a different interpretation wholly inconsistent with ATO TR 2005/8. Look at Paragraphs 69 and 88.

UPDATE: 01/06/2020

It has recently been discovered that the 1966 Defense Agreement, explained in more detail below, was neither signed by the President of the United States not ratified by the United States Senate. As such, it has absolutely no force or effect under U.S. law. As such, the IRS has no grounds to argue for its enforcement, and all Closing Agreements are invalid for Material Misrepresentation of Law.

Any reference herein to the 1966 Defense Agreement should be read consistently with this new information.

Introduction

The conclusion of this article is that employees of defense contractors at JDFPG can claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion under Section 911 of the Internal Revenue Code. However, this also applies to other military facilities around the world. If you are a former, current, or prospective employee of a defense contractor at Pine Gap or another military facility, contact our firm to schedule a free consultation by clicking here.

If you'd like to read the recent Class Action against JDFPG defense contracting companies, click here.

Background

In 1966, the United States and Australia signed a non-binding agreement entitled “Agreement between the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia and the Government of the United States of America relating to the Establishment of a Joint Defence Space Research Facility” (herein referred to as the “1966 Defense Agreement”). Article 9, Paragraph 2, of the 1966 Defense Agreement declared that Americans that are “in Australia solely in connection with the establishment, maintenance, or operation of the [Joint Defense] Facility shall not be considered” residents for purposes of Australian taxation.[1] There were no conditions for this provision. It is law. That provision effectively prevented residence-based taxation, which would have otherwise compelled Americans to report worldwide income to the Australian Tax Office (ATO). However, even for nonresidents, it has always been a rule of international law that wages are sourced and taxed in the geographic area wherein the physical performance of services giving rise to the wages was performed. In other words, wages earned in Australia would be taxed in Australia. For that reason, the 1966 Defense Agreement also included Article 9, Paragraph 1, which held that wages earned at the Joint Defense Facility at Pine Gap (JDFPG) “shall be deemed not to have been derived in Australia, provided that it is not exempt, and is brought to tax, under the taxation laws of the United States.”[2] While there is a distinction between an exemption and an exclusion for U.S. tax purposes,[3] this article will not address it.

The 1966 Defense Agreement made it clear that, in order to prevent exposure to Australian taxation on wages earned at JDFPG, an individual should not claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion. That was the contractual trade: Australia would surrender its inherent right to tax wages earned on their soil if the Americans did not claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion.

However, that all changed with the signing of the “Convention Between the Government of the United States of America and the Government of Australia for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income” (herein referred to as the “1982 Income Tax Treaty” or the “U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty”).

The Later-in-Time Rule

The United States Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit found that Congress intended to codify the “later-in-time” principle when it enacted Section 7852(d)(1), which focuses on timing to find which controls regardless of whether there is a conflict between two treaties.[4]

The 1966 Defense Agreement came before the 1982 Income Tax Treaty. The 1982 Income Tax Treaty came later. Moreover, the 1982 Income Tax Treaty specifically addressed cross-border tax implications between the U.S. and Australia. Both are treaties; the income tax treaty came later and specifically addressed governmental-type work, which includes private contractors overseas. Therefore, it controls as being both later-in-time and more comprehensive and specific to tax matters and was signed by the Secretary of the Treasury; case closed.

Even more compelling is the added fact that the technical explanations to the income tax treaties specifically address the tax implications for individuals working for private defense contracting companies performing governmental functions on behalf of their country while in another country, which is the exact situation Americans at JDFPG find themselves in.

For example, the Technical Explanations to Article 19, Paragraph 1, of the U.S.-U.K. Income Tax Treaty states “This paragraph follows the OECD Model, but differs from the U.S. Model in applying only to government employees and not to independent contractors engaged by governments to perform services for them.” The U.S.-U.K. Income Tax Treaty specifically excludes employees of private contractors from the “government service” article.

On the other hand, the Technical Explanations to Article 19, Paragraph 1, of the U.S.-Italy Income Tax Treaty states “Unlike the OECD Model , the paragraph applies both to government employees and to independent contractors engaged by governments to perform services for them.” The U.S.-Italy Income Tax Treaty specifically includes employees of private contractors in the “government service” article.

The Technical Explanations to Article 22 of the U.S.-Korea Income Tax Treaty states “Under this article, wages, salaries, and similar remuneration, including pensions or similar benefits, paid from public funds of one Contracting State to a citizen of that Contracting State for labor or personal services performed as an employee of that Contracting State or instrumentality thereof in the discharge of governmental functions will be exempt from tax by the other Contracting State.” The U.S.-Korea Income Tax Treaty extends to instrumentalities of the state performing governmental functions. The use of the term “governmental functions” could possibly imply non-government employees performing functions of a governmental nature. Nevertheless, the use of the phrase “paid from public funds” appears to require payment directly from the government, which would presumably exclude employees of private contractors. This could reasonably be rebutted with the fact that the principal-agent relationship between the U.S. government and defense contractors could qualify as an indirect payment from public funds.

The Technical Explanations to Article 18, Paragraph 1, of the U.S.-Japan Income Tax Treaty states “This paragraph follows the OECD Model, but differs from the U.S. Model in applying only to government employees and not to independent contractors engaged by governments to perform services for them.” The U.S.-Japan Income Tax Treaty specifically excludes employees of private contractors in the “government service” article.

The Technical Explanations to Article 19, Paragraph 1, of the U.S.-Germany Income Tax Treaty states “Article 19 of the Convention includes payments in respect of services rendered in connection with a business carried on by the governmental entity paying the compensation or pension.” The U.S.-Germany Income Tax Treaty specifically includes employees of private contractors in the “government service” article.

The Technical Explanations to Article 18, Paragraph 1, of the U.S.-Belgium Income Tax Treaty states “The paragraph applies to anyone performing services for a government, whether as a government employee, an independent contractor, or an employee of an independent contractor.” The U.S.-Belgium Income Tax Treaty specifically includes employees of private contractors in the “government service” article.

All of these examples of income tax treaties specifically addressing whether employees of private contractors are covered by the income tax treaty article on government service wages is intended to dispel the oft-repeated myth that income tax treaties do not address this topic. The income tax treaties with the United Kingdom, Italy, Korea, Japan, Germany, and Belgium all specifically address the topic. On that basis, the income tax treaties are more specific and later-in-time. This establishes the indisputable conclusion that the 1982 U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty controls. Furthermore, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit has also explained that treaty extensions and even amending protocols relate-back to the original effective date, so an extension or an amending protocol does not alter the outcome of the later-in-time analysis.[5] Having established that, we now look at the content of the U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty.

The Technical Explanations to Article 19, Paragraph 1, of the U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty states “This article provides that remuneration, including pensions, paid by one of the Contracting States or a political subdivision, local authority or agency thereof to a citizen of that State for the performance of governmental functions is exempt from tax by the other State.” The U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty extends to an “agency” of one of the countries. Defense contracting companies have a classic principal-agent relationship with the U.S. government. The use of the term “governmental functions” implies non-government employees performing functions of a governmental nature. And unlike other treaties, it further expands on the term by clarifying that “[w]hether functions are of a governmental nature is determined by reference to the concept of a governmental function in the State in which the income arises.” Unless the Commonwealth of Australia is prepared to argue that global electronic surveillance by the U.S. National Security Agency is a function traditionally performed by private businesses, it is clear that private contractors of defense companies are performing governmental functions. Should they challenge this, it becomes a question of fact that can be established by compelling the production of documentation and testimony from the individuals at JDFPG through a federal court’s discovery process, which they will undoubtedly and rightfully object to on grounds of national security that will serve to prove our position regarding the governmental nature of the work being done at JDFPG.

Article 19 Reserves Taxing Rights to the United States

The U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty, Article 19, reads "[w]ages, salaries, and similar remuneration… paid from funds of one of the [the United States]… or… an agency or authority [thereof]… for labor or personal services performed as an employee in the discharge of governmental functions to a citizen of [the United States] shall be exempt from tax by [Australia]."

Who defines what constitutes an “agency or authority” of the United States?

If both the U.S. and the treaty partner were OECD members when the Treaty and the commentary were drafted, courts will use the OECD commentary to interpret income tax treaties.[6] All treaties except those with Italy, Malta, Trinidad, and Pakistan are mandatorily required to defer to the OECD for proper legal interpretation in accordance with international law.

The OECD’s published commentary suggests independent contractors are not covered: “[T]he scope of the Article applies to State employees not to persons rendering independent services to a State.”[7] However, this is because the OECD Model Income Tax Treaty differs from the U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty in that it does not include the reference to an “agency or authority” of the United States. Therefore, because of this difference, it is not appropriate to defer to the OECD commentary. Instead, we must identify the intent of including the phrase “agency or authority.” This intent is illustrated in the Technical Explanations to Article 19 of the U.S. Model Income Tax Treaty: “The paragraph applies to anyone performing services for a government, whether as a government employee, an independent contractor, or an employee of an independent contractor.”

This conclusively establishes that employees of private defense contractors are covered by the scope of Article 19 of the U.S.-Australia Income Tax Treaty. Nevertheless, many employees at JDFPG have been involuntarily compelled to sign Closing Agreements that the defense companies and IRS claim are binding to deny the individual the right to claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion.

The Invalid Closing Agreements

The IRS has a long and sad history of being defeated in court on Closing Agreements because, quite frankly, they don’t seem to understand basic contract law.

In 2003, in a heated legal dispute between the IRS and a taxpayer, Treasury argued that IRS Form 987 prevented the court from examining the issue. The courts disagreed and threw their closing agreement in the trash can.[8] Same happened in 1994 when the IRS argued IRS Form 2751-AD Closing Agreement was binding.[9] Also in 1994 when the IRS argued their Form 890 and 1273 Closing Agreements were valid.[10]

What our attorneys have heard from JDFPG employees is the classic Godfather approach to acquiring a signature on a contract: “sign it or else.” Contract Law 101: acquiring a signature with threats and duress to the signer invalidates the contract. We’ve also heard of people signing the Closing Agreement contract before they departed the U.S. but after they had already rented out their home and withdrew their children from their schools. That also invalidates the Closing Agreement contract since it was acquired under duress. And lastly, we’ve heard of people signing to renew it while already living and working in Alice Springs. That doesn’t matter since there was material misrepresentation regarding your legal obligations. Material misrepresentation of fact or law also invalidates any contract.

In other words, the “closing agreements” are not worth the paper they’re printed on, and no judge in the United States would ever enforce it without being immediately overruled on appeal.

Conclusion

All of the foregoing gets us to the position where (1) the 1982 Income Tax Treaty superseded the 1966 Defense Agreement with regard to the Treaty’s Article 9, Paragraph 1, position on the taxation of wages earned at JDFPG, (2) employees of private defense contracting companies at JDFPG are covered by Article 19 of the 1982 Income Tax Treaty, and (3) the closing agreements are invalid as a matter of law; all of which permits an American employee of JDFPG to claim the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion.

However, it is critical to note that these complex treaty-based legal positions must absolutely be disclosed on the federal income tax return on IRS Forms 8275 and 8833. If these disclosure are not included, the IRS is within its right to deny the claim.

If you are a current, prior, or prospective employee at JDFPG, please contact our law firm for a free consultation.

Legal Disclosure

This article is not legal advice. It is improper to rely on this article as legal advice. In the U.S. tax system, generally, only a paid consultation or formal written tax opinion can be used as an affirmative defense to penalties. Free consultations may not be relied upon as legal advice for the purpose of avoiding penalties. The objective of a free consultation is to determine the client’s issue, fact pattern, and whether the firm can provide a legally viable solution with a minimum of Substantial Authority to support it.

Confidence Level Disclosure

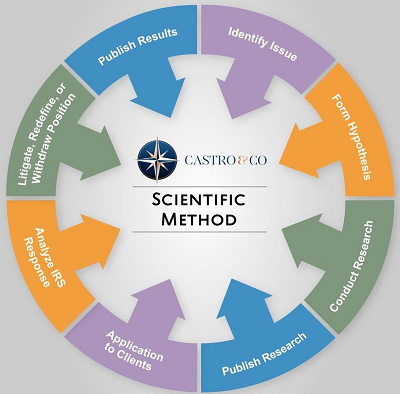

For over 3600 years, the scientific method has been used by innovative individuals as an empirical method of acquiring knowledge. In the world of tax law, it is no different. In some cases, we offer free consultations to identify the issue, form a hypothesis, conduct legal research to work toward developing a possible solution, publish our research, apply the legal theory to a client’s real-world situation, analyze the administrative response from the IRS, and then decide whether to litigate, redefine, or withdraw the position.

If the IRS points out something we had previously not considered and the legal position cannot be redefined to cure the issue, then we would withdraw the position and issue a notice to any clients to whom it applied. If, however, the position can be cured by redefining the position, then we will do so assuming the clients’ facts support the redefinition. This would, of course, entail contacting the client to seek clarification. If, however, we do not agree with the IRS response, then we will pursue litigation to seek judicial clarification in our favor.

The Scientific Method helps our tax system mature, develop, and improve by asking new questions and developing new interpretations of our tax code, answering previously unanswered questions, testing these legal theories in the federal judiciary, and eliminating ambiguity through judicial clarification. Judicial clarification even helps eliminate the need of tax attorneys who financially benefit from legal ambiguity. A fair and balanced tax system is one that is clear and concise with zero ambiguity. This can only be achieved through judicial clarification.

In the U.S. legal system, the "strength" of a legal interpretation can be quantified based on the amount of legal support for the interpretation. While a portion of this quantification is certainly subjective based on the reviewer’s legal interpretative philosophy, it is indisputable that a quantified range that encompasses all interpretative philosophies can be established. In some cases, this range can vary wildly. The importance of the level of legal authority is that it determines when penalties will and will not apply as well as when disclosure is and is not required to avoid said penalties. The range of levels of legal confidences are, from weakest to strongest, Reasonable Basis, Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, Should, and Will. In actual practice, a “Will” level opinion is never sought out by taxpayers since that would simply be a reiteration of basic textbook principles of the tax code. Likewise, a “Reasonable Basis” level opinion is rarely issued since, absent a compelling political or social purpose, it is highly unlikely to prevail in court. If, however, the topic of the “Reasonable Basis” opinion implicates a compelling political or social issue, such as the deduction for child care expenses, then our confidence in our ability to sway the federal judiciary increases, and we are, therefore, much more confident in asserting said legal position before the federal judiciary. This leaves only three confidence levels: Substantial Authority, More Likely Than Not, and Should. These are the three confidence levels within which our firm primarily operates.

A “Substantial Authority” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a 35 percent to 49 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “More Likely Than Not” opinion means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a greater than 50 percent chance of succeeding on the merits. A “Should” opinion, which is the threshold of opinion expressed in this letter, generally means that, if contested by the Service, the position advanced has a chance greater than 70 percent of success on the merits. It is important to note that these quantifications themselves are hotly contested, which implicates “void of vagueness” concerns.

The confidence level of the legal interpretation expressed in this article is: Should.

Bluebook Citation

Tax Treatment for American Contractors Employed at the Joint Defense Facility at Pine Gap, Int’l Tax Online Law Journal (December 20, 2018) url.

Legal Citations

[1] The full provision reads as follows: “Where the legal incidence of any form of taxation in Australia depends upon residence or domicile, periods during which such contractors, sub-contractors, personnel and dependants [sic] are in Australia solely in connection with the establishment, maintenance or operation of the facility shall not be considered as periods of residence therein, or as creating a change of residence or domicile, for the purposes of such taxation.”

[2] The full provision reads as follows: “Income derived wholly and exclusively from performance in Australia of any contract with the United States Government in connection with the facility by any person or company (other than a company incorporated in Australia) being a contractor, sub-contractor, or one of their personnel, who is in or is carrying on business in Australia solely for the purpose of such performance, shall be deemed not to have been derived in Australia, provided that it is not exempt, and is brought to tax, under the taxation laws of the United States. Such contractors, sub-contractors and personnel, and the dependants [sic] of any of the above other than those persons who, immediately before becoming dependants [sic], were and at all times thereafter have continued to be ordinarily resident in Australia, shall not be subject to Australian tax in respect of income derived from sources outside Australia.”

[3] The lifetime estate tax exemption prevents estate taxation on a certain portion of an individual’s estate, but it does not outright exclude an estate from estate taxation. On the other hand, the annual gift tax exclusion entirely prevents taxation on the stated amount in the Code. However, the 1966 Defense Agreement uses the term “exempt,” which would arguably include an exclusion, such as the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion. Furthermore, the Foreign Earned Income Exclusion appears to have been the focus and intent of the signatories to the 1966 Defense Agreement.

[4] See Kappus v. C.I.R., 337 F.3d 1053, 1057 (D.C. Cir. 2003) (citing S. Rep. No. 100-445, at 316-28 (1988).

[5] Id.

[6] See Podd v. C.I.R., 76 T.C.M. (CCH) 906 (T.C. 1998) (citing U.S. v. A.L. Burbank & Co., 525 F.2d 9, 15 (2d Cir. 1975); North W. Life Assurance Co. of Canada v. C.I.R., 107 T.C. 363 (1996); Taisei Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. C.I.R., 104 T.C. 535, 546 (1995) (construing the Convention for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income, Mar. 8, 1971, U.S.-Japan, 23 U.S.T. 969, with reference to the Model Treaty and its commentary)).

[7] 2014 OECD Commentary on Article 19, Paragraph 2.1.

[8] See Sunik v. C.I.R., 321 F.3d 335 (2d Cir. 2003) (Form Letter 987 did not constitute a closing agreement, despite misleading language in the letter).

[9] See Stutz v. I.R.S., 846 F. Supp. 25 (D.N.J. 1994) (Form 2751-AD is not considered a closing agreement; no "final and conclusive" language on form; no reference to 26 U.S.C.A. 7121 on form).

[10] See Estate of Barrett v. C.I.R., T.C. Memo. 1994-167 (1994) (neither Form 890 nor Form 1273 constitutes closing agreement). Also see these cases: Hudock v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 65 T.C. 351 (1975) (Form 4549 does not constitute closing agreement.); Vitale v. C.I.R., T.C. Memo. 1988-233 (1988) (form 3547 executed by skilled attorney was not intended to be closing agreement); Wasserstrom v. C.I.R., T.C. Memo. 1986-417 (1986) (Form 1902-E does not constitute closing agreement).