There was once a time when everyone was wholly convinced that the world was flat.

This is a phrase we often repeat to skeptics. Today, the prevailing opinion among tax attorneys, CPAs, and tax professionals in general is that there is no way around Section 965’s Deemed Repatriation Tax.

Aside from an Article 1, Section 9, Clause 3 “ex post facto” constitutional challenge[1] to the enforceability of Code section 965(a)(1)’s retroactive application to November 2 before the bill was signed into law, it has been universally accepted in the tax industry that there is no way to lawfully avoid the application of Section 965. If you’re a U.S. tax resident and own or control 10% or more of the voting power of a controlled foreign corporation, you must include in income the greater of the accumulated E&P as of November 2 or December 31, 2017. If a United States corporation owned or controlled 10% or more of the voting power of any foreign corporation anywhere in the world regardless of its status as a CFC or not, it must include in income the greater of the accumulated E&P as of November 2 or December 31, 2017.

Every law firm in the U.S. is wholly convinced Section 965 is an airtight provision. Nothing could be further from the truth. Allow this author to illuminate the solution in five simple words: “retroactive check-the-box election.” If you don’t already see where I’m going with this, pay close attention. For detailed information on claiming back a refund of any Section 965 tax you have paid, click here.

I.Introduction

Treasury regulations applicable to the Internal Revenue Code and the IRS provide rules for when a foreign business entity will be treated as either a corporation or a pass-through entity by default (without an election) for federal income tax purposes. An eligible foreign entity may elect to change or confirm its default classification for tax purposes by filing IRS Form 8832 within 75 days of the desired effective date of the classification.

Entity Classification

In the late 1990s, the IRS and Treasury published entity classification regulations under Code section 7701 (check-the-box regulations) that were designed to simplify the lives of both taxpayers and the government.

While a few business entities are automatically classified as corporations, most can choose how they will be classified for federal tax purposes. A business entity is any entity recognized for federal tax purposes that is not properly classified as a trust under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-4 or otherwise subject to special treatment under the Code. Business entities that are not classified as a corporation under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2 are “eligible” entities.

Eligible entities can make a classification election. An eligible entity with at least two members can choose to be classified as either (1) an association taxable as a corporation or (2) a partnership. An eligible entity with a single member can choose to be (1) classified as an association taxable as a corporation or (2) disregarded as an entity separate from its owner. If a joint undertaking is considered an entity separate from its owners for federal tax purposes and is an eligible entity, it may elect how it will be classified under these same rules.

Automatic Classification as a Corporation

Under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2, the following business entities are automatically classified as corporations: Organizations formed under a federal or state law (or under a statute of a federally recognized Indian tribe) that refers to the entity as incorporated or as a corporation, body corporate, or body politic; Associations, as determined under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3, including Sec. 501(a) exempt organizations; Organizations formed under a state law that refers to them as joint-stock companies or joint-stock associations; Insurance companies; Certain state-chartered banks; Organizations wholly owned by a state or local government or by foreign governments or entities described in Temp. Treas. Reg. § 1.892-2T; Organizations specifically required to be taxed as corporations under Code sections other than Sec. 7701(a)(3) (e.g., certain publicly traded partnerships); Foreign organizations identified in Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(b)(8) and business entities formed under the laws of U.S. territories and possessions; Real estate investment trusts; Entities created or organized under more than one jurisdiction (i.e., business entities with multiple charters), if the entity is treated as a corporation by any one of these jurisdictions; and Other organizations electing to be classified as corporations by filing Form 8832, Entity Classification Election (Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3).

Entities with More Than One Owner

As previously stated, an eligible entity with at least two members is treated as a partnership or as an association taxable as a corporation.

Single Owner Entities

As noted, an eligible entity with a single member can choose to be classified as either (1) an association taxable as a corporation or (2) disregarded as an entity separate from its owner.

Note: If the single owner of a business entity is a bank, the special rules applicable to banks under the Code (excluding Secs. 864(c), 882(c), and 884) continue to apply to the single owner, as if the wholly owned entity were a separate entity (Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(c)(2)(ii)).

Disregarded Entities

In general, a disregarded entity is an eligible entity treated as an entity not separate from its single owner. However, a disregarded entity is treated as separate from its owner for purposes of:

Federal tax liabilities of the entity for any tax period for which the entity was not disregarded;

Federal tax liabilities of any other entity for which the entity is liable; and

Refunds or credits of federal tax (Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(c)(2)(iii)).

A disregarded entity is also separate from its owner for purposes of employment tax (Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(c)(2)(iv)(A)) and many excise taxes (Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(c)(2)(v)), but not for self-employment tax.

Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(a) provides in part that an entity that is not a per se corporation under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(b)(1), (3), (4), (5), (6), (7), or (8) (i.e., an eligible entity) may elect its classification for federal tax purposes as provided in Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3. An eligible entity with at least two members can elect to be classified as either a partnership or corporation, and an eligible entity with a single owner can elect to be classified as a corporation or disregarded entity.

Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(b) provides a default classification for an eligible entity that does not file an entity classification election. Thus, an entity classification election is necessary only when an eligible entity chooses to be classified initially as other than its default classification or when an eligible entity chooses to change its classification.

IRS Form 8832

Entity classification elections are made by filing IRS Form 8832, Entity Classification Election. Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(c)(1)(iii) provides that an entity classification election will be effective on the date specified on the form or on the date filed if no such date is specified on the election form. The effective date specified on Form 8832 must be no more than 75 days before the filing date and no more than 12 months after the filing date. In other words, no more than 75 days retroactive from the day you mailed it off and no more than 12 months in advance. For example, if you mail IRS Form 8832 to the IRS on July 1, 2018, the effective date listed on the form cannot be earlier than April 17, 2018 and cannot be later than July 1, 2019.

As previously noted, a business entity not classified as a corporation can elect its classification under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3. An eligible entity with at least two members can elect to be classified either as an association (and thus as a corporation under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2(b)(2)) or as a partnership, and an eligible entity with a single owner can elect to be classified as an association or to be disregarded as an entity separate from its owner. Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(b) provides a default classification for an eligible entity that does not file an entity classification election. Thus, an election need only be made when an eligible entity chooses to be classified initially as other than its default classification or when an eligible entity chooses to change its classification.

Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(c)(1)(i) generally provides that an eligible entity may elect to be classified other than as provided under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(b), or to change its classification, by filing Form 8832 with the appropriate IRS service center. An election will not be accepted unless all of the information required by the form and instructions (including the entity’s taxpayer identification number) is provided.

Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(c)(1)(ii) provides that an eligible entity required to file a federal tax or information return for the tax year for which an election is made must attach a copy of its Form 8832 to its federal income tax or information return for that year. If the entity is not required to file a return for that year, a copy of its Form 8832 must be attached to the federal income tax or information return of any direct or indirect owner of the entity for the owner’s tax year that includes the date on which the election was effective.

An eligible entity may be eligible for late election relief under Rev. Proc. 2009-41. If Rev. Proc. 2009-41 does not apply, an entity may seek relief for a late entity election by requesting a letter ruling and paying a user fee (following Rev. Proc. 2018-1 or any successor revenue procedures).

Change in classification

If an eligible entity elects to change its classification, the entity cannot change its classification by election again during the 60 months succeeding the effective date of the election. However, the IRS may permit the entity to change its classification by election within the 60-month period, if more than 50% of the ownership interests in the entity as of the effective date of the subsequent election are owned by persons that did not own any interests in the entity on the filing date or on the effective date of the entity’s prior election. An election by a newly formed eligible entity that is effective on the date of formation is not considered a change for these purposes.[2]

Section 9100 Relief

Under Treas. Reg. § 301.9100-1(c), the IRS may grant a reasonable extension of time to make certain elections. Treas. Reg. § 301.9100-3 provides that the IRS will generally grant an extension of time when the taxpayer provides the evidence to establish to the satisfaction of the IRS that the taxpayer has acted reasonably and in good faith and the grant of relief will not prejudice the interests of the government.

Generally, a substantial reduction in tax is deemed to prejudice the interests of the government.

Revenue Procedure 2002-59

Under prior law, if a new foreign business entity was created, it would have 75 days from its date of creation to file an entity classification election. This was very burdensome for business owners who didn’t consult with a tax attorney. As a result, many entities were failing to timely file entity classification elections within 75 days of creation since that’s understandably the last thing on their minds when starting a new business, so the IRS published Revenue Procedure 2002-59, which provided guidance for how a newly formed entity could request relief when it files its first income tax return.

Under these now old rules (Rev. Proc. 2002-59), the foreign entity could request relief by filing the Form 8832 with an attached statement along with its first income tax return explaining that the taxpayer had “reasonable cause” for not making the election on time. While not automatic, this relief was generally granted by the IRS. However, in order to be eligible for this simple procedure, the election had to be (1) for an entity which was newly formed under local law, and (2) filed before the due date for the first federal tax return (not including extensions).

If, however, the error was discovered beyond the due date, the only available recourse was to file a request for a Private Letter Ruling (PLR), which was far more complex for most law firms and costly to clients. Similarly, if the foreign entity was not newly formed but acquired (e.g., as a dormant shelf company), the only recourse for failing to file beyond the due date was to request a PLR.

Extension to Changes in Classification

Revenue Procedure 2009-41 superseded Revenue Procedure 2002-59. The idea was to make it easier to obtain relief for the late filing of a check-the-box election by extending the grace period during which taxpayers could use a more simplified method of obtaining relief instead of having to apply for a PLR.

In Revenue Procedure 2009-41, the IRS extended late election relief to changes in entity classification and provided instructions on how to obtain a late entity classification election retroactively up to 3 years and 75 days

Income Tax Implications of a Check-the-Box Election

Under Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(g), if an eligible entity classified as a corporation elects to change its classification to be treated as a disregarded entity (disregarded entity election), the corporation is deemed to liquidate by distributing all of its assets and liabilities to its single owner (the deemed liquidation). The tax treatment of the deemed liquidation is determined under all relevant provisions of the Code and general principles of tax law, including the step-transaction doctrine.

Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(g)(3) (the effective date provision) provides that the deemed liquidation occurs immediately before the close of the day before the effective date of the disregarded entity election. Thus, if an entity classified as a corporation files a disregarded entity election effective on January 1, the deemed liquidation is treated as occurring immediately before the close of December 31.

II.Check-the-Box Strategies in International Tax Planning

Because this author can already hear the naysayers snickering, let me explain how check-the-box strategies have already been used in the field of international tax planning for over 20 years.

Introduction

In the early 2000s, the check-the-box regulations introduced numerous planning opportunities in cross-border transactions. This section describes variations on three types of check-the-box planning strategies used in international transactions and discusses the technical issues they raise under present law.

Delayed Section 351 with a Delayed Check-the-Box Election to Soak-Up Start-Up Losses

Hypothetical Transaction Details

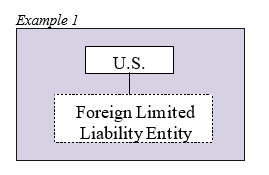

An example of a check-the-box planning strategy is that of a U.S. corporation (“U.S. Corp”) that invests in a new hydroelectric plant in country A, which provides a lengthy tax holiday for renewable energy companies. U.S. Corp establishes a newly formed Country A limited liability entity, contributes significant equity to the entity and elects for the entity to be disregarded for U.S. tax purposes. The entity borrows substantial amounts from third parties to finance the plant.

U.S. Corp uses losses resulting from interest expense and depreciation in the early years of the plant’s operations. Once the business becomes profitable, U.S. Corp makes a new election to treat the foreign entity as a corporation for U.S. tax purposes. As a result, after including in income any loss recapture and other amounts required under Section 367(a), U.S. Corp obtains the benefit of deferral on subsequent earnings from the plant that are not subpart F income and enjoys the benefit of the country A tax holiday without offsetting U.S. tax. The election has absolutely no effect in Country A.

Issues Under Present Law

This election to convert the foreign entity from a disregarded entity to a corporation for U.S. tax purposes raises questions about whether any Section 351 business purpose requirement is met, and whether the IRS could assert that the principle purpose of the transaction was tax avoidance, and thus invoke Section 269(a)(1) to deny the intended tax results.

Section 351 Business Purpose Requirement

While Section 351 itself and the regulations thereunder do not contain a specific business purpose requirement, the IRS takes the position that such a requirement exists, albeit at a relatively low threshold compared to tax-free reorganizations.[3] The courts have at times applied a business purpose requirement to deny Section 351 treatment, resulting in the transferor either recognizing gain, not being able to claim losses, or being treated as continuing to be the owner of the transferred property.[4] But, in these situations, generally the transferred property was held very briefly by the transferor and/or the transferee, there was a pre-arranged plan to dispose of the property, the transferee corporation was a shell whose existence was transitory, and/or the transfer primarily benefited the transferor.[5] None of these factors are present when a U.S. corporation that has been operating a foreign trade or business contributes that business to a foreign corporation in order to defer tax on an uncertain amount of income going forward. As a result, if U.S. Corp instead transferred the power plant to a second, controlled foreign limited liability entity that had elected to be treated as a corporation for U.S. tax purposes, the transfer would clearly pass muster under Section 351, notwithstanding its tax motivation.

The question instead presented by this hypothetical is whether accomplishing the same tax result by checking the box on an entity that existed since the initiation of the business can also satisfy any business purpose requirement, given that a tax election inherently has only tax effects.

Application of Section 269

The second question is whether Section 269 would, instead or in addition, apply to deny the intended tax results. As a general matter, the IRS interprets Section 269 broadly enough to apply to the acquisition of control of a corporation to reduce tax on its income. In particular, several cases apply Section 269 to the formation of a corporation for the principal purpose of tax avoidance. These cases typically involve transfers intended to obtain deductions and credits.[6] At least one case, however, considered the formation of a foreign corporation to hold a foreign joint venture interest. It held that the transaction was not subject to Section 269 because Section 269 does not apply to the tax benefit of obtaining deferral on foreign business income.[7]

More to the point, several cases refuse to apply Section 269 to acquisitions of control of corporations where Congress intended for taxpayers to obtain the tax benefits resulting from the transfer.[8] These cases provide a strong basis for concluding that an actual transfer of foreign business assets to a foreign corporation should not be subject to Section 269 given the detailed statutory rules Congress has enacted over the years governing the taxation of foreign corporations, acquisitions of foreign corporations and transfers of assets to such corporations. Nevertheless, in the case of a check-the-box transaction, where the acquisition of control and asset transfer for tax purposes is not accompanied by any actual acquisition of control and asset transfer, the non-application of Section 269 is not entirely clear.

Thus, even though the IRS is unlikely to assert that the intended tax consequences of an actual contribution parallel to the hypothetical should be denied under Section 269(a)(1), the question arises of whether the IRS should do so in the case of the check-the-box transaction described above.

Policy Analysis

Because check-the-box elections apply purely for tax purposes, the IRS and courts should agree that the tax consequences of a valid election are not subject to any business purpose or principal purpose type test. The IRS granted the election without restriction; requiring a business purpose or any nontax purpose to claim the associated tax consequences would merely serve to deny what the IRS plainly granted. Instead, if the IRS and the Treasury would like to alter the consequences of the election, they should do so through the terms, conditions and scope of the election itself, not by applying a business purpose or nontax purpose requirement to its consequences.

Does that mean that taxpayers should be able to avoid otherwise potentially serious issues under Section 351 or Section 269 by undertaking a transaction through a check-the-box election? This is an important question. The above example does not present this question squarely because an actual transaction would pass muster under both sections; accordingly, it is clearly appropriate to conclude that the normal tax consequences of a parallel check-the-box transaction should be allowed.

Check-and-Sell Transactions

Description of Basic Transactions

The second set of examples of check-the-box planning strategies are check-and-sell transactions. There are two general varieties.

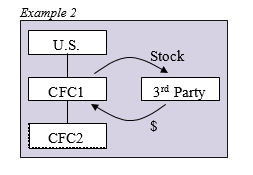

In the first, illustrated above, a first-tier CFC checks the box on a second-tier CFC to treat it as a disregarded entity. The first-tier CFC then sells the stock of the second-tier CFC to an unrelated foreign party. As a result of the election, the transaction is treated as an asset sale instead of a stock sale, meaning that the transaction does not generate subpart F income, except to the extent that selling the assets would generate subpart F income. Checking the box also changes the character of the income from the transaction to overall basket income for foreign tax credit purposes to the extent that the assets of the second-tier CFC generated overall basket income prior to the transaction.

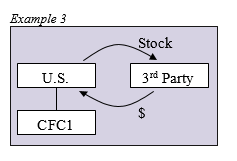

In the second type of check-and-sell transaction, illustrated above, a U.S. parent checks the box on its first-tier CFC and then sells that CFC’s stock to an unrelated foreign party. As above, the U.S. parent treats the transaction as an asset sale instead of a stock sale, which changes the character of the income to overall basket income for foreign tax credit purposes to the extent that assets of the CFC generated overall basket income.[9] In addition, if the CFC has losses, the election would generally render the losses ordinary under Section 1231 instead of capital under Section 1221. However, Section 836 of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 (the “Jobs Act”)[10] appears to limit the possibility of the U.S. parent claiming a Section 1231 loss on any of the assets transferred in such circumstances, unless sufficient Section 1221 gains exist on other assets to avoid the provision.

Issues Under Present Law

Several efforts have been made over the past few years to eliminate the intended tax consequences of these transactions. One such effort culminated in the 1999 issuance of proposed regulations that would have invalidated an election to treat a subsidiary as a disregarded entity if a 10-percent-or-greater interest in the subsidiary was disposed of within one year of the election (or one day prior to the election), and if the subsidiary had been treated as a corporation at some point during the year prior to the disposition.[11] This provision would have reversed the favorable tax consequences of both of the transactions described above. However, it was dropped when the proposed regulations were finalized in 2003, following criticism that it was overly broad and undercut the effort underlying the check-the-box regulations to promote certainty regarding entity classification. At that time, the IRS announced that instead of following the approach of the proposed regulations of changing the classification of an entity in certain situations, it would focus on ensuring that the substantive rules of the Code and U.S. tax treaties reach appropriate results, regardless of changes to an entity’s classification.[12]

The next major effort to eliminate the tax benefits of check-and-sell transactions occurred in the pivotal Dover case.[13] In Dover, the facts mirrored Example 2 above. The U.S. taxpayer owned a first-tier UK CFC (“CFC1”), which in turn owned a second-tier UK CFC (“CFC2”) that was engaged in an elevator installation and servicing business. CFC1 sold CFC2 to an unrelated foreign party, and then requested Section 9100 relief to retroactively file an election for CFC2 to be treated as a disregarded entity for U.S. tax purposes effective immediately prior to the sale. Somewhat surprisingly, the IRS granted the taxpayer’s request but noted that its decision had no bearing on whether gain from the sale of CFC2 generated Subpart F income.

Ultimately, the case was litigated, and the taxpayer claimed that the sale did not generate subpart F income because CFC1 had sold assets used in its trade or business. In support of its position, the taxpayer cited IRS guidance providing that when assets of a subsidiary are sold following its Section 332 liquidation, the subsidiary’s trade or business is attributed to its parent.[14]

The IRS conceded that the transaction was an asset sale because the check-the-box election resulted in a deemed Section 332 liquidation followed by a deemed sale of CFC2’s assets; however, the IRS argued that the assets had not been used in CFC1’s trade or business, that CFC2’s trade or business should not be attributed to CFC1, and, therefore, that the proceeds still constituted Subpart F income. In support of its position, the government cited Acro Manufacturing, which held that the sale of a subsidiary’s assets used in its trade or business on the same day as its actual Section 332 liquidation resulted in capital income.[15] Contrary to existing guidance, Acro Manufacturing thus implied that when the assets of a subsidiary are sold shortly after its liquidation, the trade or business of a subsidiary is not attributed to its parent.

In Dover, the court decided in favor of the taxpayer on the basis that the IRS’s position was inconsistent with its existing guidance that a subsidiary’s trade or business is attributed to its parent as part of a Section 332 liquidation. While Judge Halpern declined to revisit Acro Manufacturing, he did note that the IRS, in effect, rejected the court’s position in Acro Manufacturing by issuing Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-2 and the guidance relied upon by the taxpayer.[16]

Policy Considerations

After the Dover case, all questions as to whether taxpayers are entitled to the intended tax consequences of check-and-sell transactions, aside from the limitation on converting capital losses into ordinary losses that was enacted as part of the Jobs Act, were extinguished.

Conversions of Stock Reorganizations and Transfers into Asset Reorganizations

Description of Basic Transactions

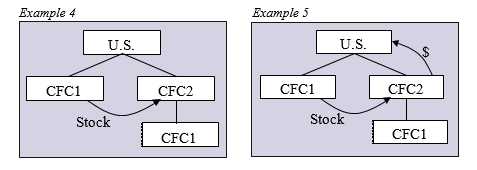

The final set of examples of check-the-box planning strategies are conversions of stock reorganizations and transfers into asset reorganizations. One way a U.S. parent can accomplish this result, as illustrated below in Example 4, is by transferring the stock of a first-tier CFC (CFC1) to another first-tier CFC (CFC2) in a manner that would qualify as a B reorganization, and then checking the box to treat CFC1 as a disregarded entity. This converts the transaction to a D reorganization. As a result, the U.S. parent can treat the transaction as a foreign-to-foreign asset transfer under Section 367(b)[17] and not an outbound stock transfer, thereby avoiding the Section 367(a) gain recognition agreement requirement.[18]

A second variety of this planning strategy, illustrated above in Example 5, involves a U.S. parent transferring the stock of a first-tier CFC (CFC1) to another first-tier CFC (CFC2) in exchange for cash from CFC1, and then checking the box to treat CFC1 as a disregarded entity. Absent this election, the transfer would be treated as a Section 304/351 transaction. But after the election, the U.S. parent can treat the transfer as a Section 368(a)(1)(D) reorganization with boot. As a result, the amount of dividend income is limited to the U.S. parent’s gain in CFC1; such dividend income is either sourced only to the earnings and profits of CFC1 or to the earnings and profits of CFC1 first, and the U.S. parent avoids any requirement for a gain recognition agreement.

Issues Under Present Law

The intended tax results of the transactions described above are fairly well established, although the IRS has expressed some interest in revisiting the results. The IRS first applied the step-transaction doctrine to treat a share transfer followed by an effective liquidation as a transfer of assets in Rev. Rul. 67-274.[19] Since then, asset transfer treatment has effectively become black letter law, with the possible exception of situations where applying the doctrine would violate clear Congressional intent.[20] In line with this position, the IRS has acknowledged that Example 4 and 5 transactions are treated as foreign-to-foreign asset transfers, and not as U.S.-to-foreign share transfers for Section 367 purposes.[21] Nevertheless, the IRS has stated that it is considering whether to expand the application of Section 367(a) gain recognition agreement requirement to apply to such transactions where the shareholder in question is a U.S. person.[22]

With respect to transfers described in Example 5, the IRS has also consistently ruled that any cash or other nonstock consideration received is boot in a C or D reorganization and thus governed by Section 356, not Section 304.[23] Moreover, the IRS and the courts have consistently treated a pure sale of shares followed by a liquidation as a D reorganization, at least where the target and the acquiring corporation are owned by the same shareholder so that the failure to issue any shares is meaningless.[24]

The application of Section 356 instead of Section 304 in these circumstances has several important consequences. First, the amount of any dividend resulting from the transaction is limited to the gain in CFC1’s shares by reason of Section 356(a)(1). Second, Section 356(a)(2) provides that any dividend is first sourced out of CFC1’s earnings and profits, and it may be limited overall to CFC1’s earnings and profits.[25] Finally, while the U.S. parent can obtain any Section 902 credits attributable to a dividend from CFC1,[26] there is no authority allowing it to treat the dividend as previously taxed income under Section 959(a). There is also no authority with respect to either Section 902 credits or previously taxed income if any portion of the dividend is attributable to CFC2’s shares.

Conclusion

This section outlined a variety of check-the-box planning strategies employed in the context of international tax planning to indisputably establish its recognition by both the IRS and courts. Now that it has been established that a mere check-the-box election can have a tremendous income tax effect, we move to the newly created Section 965 Deemed Repatriation Tax.

III.Retroactive Check-the-Box Election to Defeat Section 965

It is possible to obtain a retroactive check-the-box election to the date of creation. In other words, from the date the entity was first created, it is possible to obtain retroactive check-the-box treatment. Yes, not just 3 years and 75 days; all the way back to the date of creation. This was not specifically discussed in this article because we’re not a non-profit law firm. That’s our intellectual property that you need to pay for. Engage our firm.

To assist in making the decision whether to further explore this option, you need to determine your Section 965 Deemed Repatriation Tax. Once you complete that analysis, you will then want to calculate the average annual effective foreign income tax rate paid on that income. If the average effective foreign income tax rate over the lifetime of the entity is lower than your Section 965 Deemed Repatriation Tax, then you will want to go with the lower tax exposure afforded by a Retroactive-to-Creation Check-the-Box Election.

For closely-held companies with owners residing outside of the U.S., we recommend a retroactive-to-creation check-the-box election coupled with a Streamlined Foreign Offshore Filing Compliance submission.

For closely-held companies with owners residing in the U.S., we recommend a retroactive-to-creation check-the-box election coupled with a comprehensive engagement for the filing of income tax returns for the income and resulting foreign tax credits for all years since creation.

For large publicly traded companies, we recommend a retroactive-to-creation check-the-box election coupled with a comprehensive engagement for the filing of income tax returns for the income and resulting foreign tax credits for all years since creation.

IV.Closing

Pay no attention to the scare tactics of unethical attorneys using fear to drum-up business. Come to a law firm ready to eliminate your tax exposure; not a firm that acts more like agents of the IRS by forcing taxation on you.

Contact our team of tax attorneys, accountants, and professionals for a free consultation. Our team is ready and able to substantially reduce, if not entirely eliminate, your Section 965 Deemed Repatriation Tax exposure.

Update: To read about how this legal strategy resolves the possibility of retroactivity of Treasury Regulations promulgated under Section 965, click here.

[1] “No bill of attainder or ex post facto Law shall be passed.” Const. Art. I § 9, Cl. 3.

[2] Treas. Reg. § 301.7701-3(c)(1)(iv).

[3] Caruth v. U.S., 688 F. Supp. 1129 (N.D. Tex. 1987), aff’d sub nom., 865 F.2d 644 (5th Cir. 1989) (finding a valid business purpose when taxpayer transferred stock of Corp A to Corp B four days prior to planned declaration of dividend by Corp A).

[4] Stewart v. C.I.R., 714 F.2d 977 (9th Cir. 1983); Estate of Kluener v. C.I.R., 154 F.3d 630 (6th Cir. 1998); IRS Notice 2001-17.

[5] FSA 200134008 (May 15, 2001) (including the above in a list of factors relevant to determining whether a valid business purpose is present under Section 351).

[6] Coastal Oil Storage Co. v. C.I.R., 242 F.2d 396 (4th Cir. 1957); James Realty Co. v. U.S., 280 F.2d 394 (8th Cir. 1960).

[7] Siegel v. C.I.R., 45 T.C. 566 (1966).

[8] A.P. Green Exp. Co. v. U.S., 284 F.2d 383 (Ct. Cl. 1960) (holding that Section 269 does not apply to a transfer of assets to a Western Hemisphere Trade Corporation).

[9] Of course, the transaction would require inclusion of the all earnings and profits amount under Section 367(b) and the regulations thereunder without regard to the gain recognized on the sale.

[10] American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, PL 108–357 (October 22, 2004).

[11] Prop. Reg. § 301.7701-3(d).

[12] IRS Notice 2003-46 (Entity Classification for Certain Foreign Eligible Entities).

[13] Dover Corp. v. C.I.R., 122 T.C. 324 (2004).

[14] Rev. Rul. 77-376; Rev. Rul. 75-233; GCM 37054 (Mar. 21, 1977).

[15] Acro Mfg. Co. v. C.I.R., 39 T.C. 377 (1962), aff’d, 334 F.2d 40 (6th Cir. 1964).

[16] Dover Corp. v. C.I.R., 122 T.C. 324, 350-52 (2004).

[17] Rev. Rul. 67-274; Treas. Reg. §§ 1.367(b)-3(a), 1.367(b)-4.

[18] Treas. Reg. § 1.367(b)-3(b)(1)(ii).

[19] Rev. Rul. 67-274.

[20] Rev. Rul. 2001-46 (analyzing whether treating a qualified stock purchase followed by a merger of the acquiring company with the target as an A reorganization rather than a purchase followed by a liquidation violated the exclusivity policy of Section 338).

[21] PLR 9327010 (July 9, 1993).

[22] IRS Notice 2003-46.

[23] PLR 9550024 (Dec. 15, 1995); PLR 9349008 (Dec. 10, 1993); PLR 9327010 (July 9, 1993); PLR 9111055 (Mar. 15, 1991); PLR 8952041 (Dec. 29, 1989).

[24] Degroff v. C.I.R., 54 T.C. 59 (1970), aff’d sub nom. (10th Cir. 1971)

[25] The IRS takes the position that the acquiring corporation’s E&P is also taken into account where the target and the acquiring corporation are owned by the same shareholders. Rev. Rul. 70-240. The Fifth Circuit agreed, but then the IRS issued a Revenue Ruling disagreeing with the Fifth Circuit decision followed by a revocation of that disagreement followed by that revocation being declared obsolete in 2003. Davant v. C.I.R., 366 F.2d 874 (5th Cir. 1966); Rev. Rul. 69-185 (declined to follow Davant but later revoked in Rev. Rul. 75-561 but then the revocation was obsoleted by Rev. Rul. 2003-99). The Tax Court has, however, held that only the target’s E&P should be taken into account. Atlas Tool Co. v. C.I.R., 70 T.C. 86 (1978), aff’d sub nom., 614 F.2d 860 (3d Cir. 1980).

[26] Rev. Rul. 74-387.